Institute for Christian Teaching

Education Department, General Conference

of Seventh-day Adventists

FAITH, REASON, AND CHOICE:

LOVING GOD WITH ALL OUR MIND

Humberto M. Rasi

2nd Symposium on the Bible

and Adventist Scholarship

Juan Dolio, Dominican

Republic

March 15-20, 2004

FAITH, REASON, AND CHOICE:

LOVING GOD WITH ALL OUR MIND

Humberto M. Rasi, Ph.D.

Special Projects,

Department of Education, General Conference of Seventh-Day Adventists

“Lord, help me never to use

my reason against the truth.”

--A Jewish Prayer

One day, a scholar asked Jesus Christ to

define the most important commandment in God’s law (Mark 12:28-31).* In His reply, Jesus told him that the greatest

commandment has two parts. The first is to love God “with all your heart and

soul and mind and strength.” How do we understand this famous mandate? We love

him with all our heart when we trust in Him and devote to Him our greatest

affections, living a life according to His will. We love God with all our soul

when we cultivate a deep friendship with Him through regular communication in

prayer, Bible study, worship, and meditation. And we love Him with all our

strength when we keep our body healthy and serve others with our abilities.

But, how do we love God with all our mind?

Through

the centuries, thoughtful Christians have been intensely interested in the

proper relationship between faith and reason in the believer's life. Christians

involved in advanced studies, research, or professions that challenge the foundations

of faith continually face the dilemma of how to love God with all their mind,

integrating faith and reason in their daily activities. The tension is

heightened by the fact that many of our contemporaries assume that intelligent

people are not religious or, if they are, prefer that they keep such beliefs to

themselves.

In

this essay I will present a brief survey of the options available in

considering issues of faith and reason, review key biblical passages on the

subject, suggest how believers can deal with questions and doubts, and propose

ways in which thoughtful Christians can cultivate a reasoned faith. I will

conclude by outlining the role of personal choice in granting priority to

either faith or reason in our intellectual pursuits.

During

the first fourteen hundred years of our era the relationship between faith and

reason was not controversial in the Western world, because religious beliefs

and institutions held a privileged position in society. Acceptance of the

Christian Church, its dogmas, and traditions was assumed in the general

culture.

The

first major challenge to this hegemony occurred during the Protestant

Reformation of the 1500s. Martin Luther and others sought to restore the Bible

to a position of authority in Christian belief and practice while highlighting

the direct, personal relationship that must exist between the believer and God,

rather than through the established Church and its representatives. Although

Luther was a well-read reformer, he had misgivings about the role that

autonomous reason could play in the Christian experience. “Reason--he is

reported to have said in his mature years--is the greatest enemy that faith

has. It never comes to the aid of spiritual things, but, more frequently than

not, struggles against the Divine Word, treating with contempt all that

emanates from God.”[1]

One

century later Descartes stated that he would consider true and reliable only

what his reason accepted. And with him, the faith-reason equation in Europe

started to shift toward the latter factor. During the 1700s the Enlightenment

critically examined the role of traditional institutions and accepted beliefs,

challenging Christian dogmas and Church authority. Thinkers such as Diderot,

Hume, Montesquieu, and Voltaire paved the way for an emerging secularism. Human

rationality apart from faith in God started to gain the upper hand in

intellectual circles. Today, most educated people take for granted the supreme

value of reason and question the validity of religious faith, labeling it ignorance,

credulity, or even superstition.

Premises and definitions

According

to the Scriptures, God created Adam and Eve at the beginning of human history

and endowed them with rationality and free will, with "the power to think

and to do."[2] Exercising those abilities, our first parents disobeyed God

and, as a result, lost their perfect status and home. Although we share the

weaknesses of their fallen condition, God has preserved our capacity to think

for ourselves, exercise trust, and make choices. In fact, one of the goals of

Adventist education is "to train the youth to be thinkers, and not mere reflectors

of other men's thought."[3]

Before

proceeding, clarity requires that we define a few key terms:

Faith,

from a Christian perspective, is an act

of the will that chooses to place one’s trust in God in response to His

self-disclosure and to the promptings of the Holy Spirit in our conscience.[4]

Religious faith is stronger than belief; it includes the willingness to live

and even die for one's convictions.

Reason is the exercise of the mental capacity for rational

thought,

understanding, discernment,

and acceptance of a concept or idea. Reason looks for clarity, consistency,

coherence, and proper evidence.

Belief is the mental act of accepting as true, factual, or

real a statement, an event, or a person. Of course, it is also possible to hold

a belief in something that is not true.

Will is the ability and power to elect a particular belief

or course of action in preference to others. Choice is the free exercise

of such ability.

Reason

and faith are asymmetrically related. It is possible to believe that God exists

(reason) without believing in God or trusting in Him (faith).[5] But it is

impossible to believe and trust in God (faith) without believing that He exists

(reason).

I

accept the priority of faith in the Christian intellectual life, as expressed

in two classical formulations: Fides quaerens intellectum ("Faith

seeks understanding") and Credo ut intelligam ("I believe in

order that I may understand"). Reason is important to faith, but it cannot

replace faith. To a Christian, acquiring knowledge is not the ultimate object

of life; life's highest goal

is to know God and to

establish a personal, loving relationship with Him.[6] Such trust and friendship

leads to obedience to God and to loving service to fellow human beings.

Relationship between faith and reason

How

have believers related to issues of faith and reason in the past? How should we

relate to them? During the Christian era, individuals assumed various

approaches that can be outlined as follows:[7]

1.

Fideism: Faith ignores or

minimizes

the role of

reason in arriving at truth.

the role of

reason in arriving at truth.

According to this position,

faith in God

is the ultimate criterion of truth and all that a

Christian needs for certitude

and salvation.

Fideists affirm that God

reveals Himself to

human consciousness through

the Scriptures,

the Holy Spirit, and mystical

experience, which

are sufficient to know all

important truths. A

popular contemporary saying

summarizes this stance: "God says it. I believe

it. That settles it."

Radical

fideism was first articulated by Tertullian (160?‑230?), an early

Christian apologist known for his critical attitude toward the surrounding

pagan culture. It was the argumentative Tertullian who remarked, Credo quia

absurdum ("I believe because it is absurd"). In the succeeding

centuries other Christian authors have extolled the supreme value of blind

faith in direct opposition to human reason. Carried to an extreme, fideism

rejects rational thought, opposes advanced education and scientific research,

and may lead to a private, mystical religion.

Moderate

fideists accept that at least some truths (such as God's existence and moral

principles) may be known by human reason illumined by the Holy Spirit (John

1:9; 16:13). Reason, then, can partially comprehend religious

truths after they have been revealed. In addition, there is a rational basis

for accepting the truths of faith that the human mind cannot, on its own,

discover or fully comprehend. Such a position was articulated by the French

writer Blaise Pascal (1623‑1662). Faith predominates, but reason is not

ignored.

Critics of radical fideism observe that

faith in God and in Jesus Christ presupposes that there is a God who revealed Himself

to humanity in Christ. Furthermore, Christians who receive the Bible as a

trustworthy revelation of God must, of necessity, exercise their rational

powers to comprehend and accept the propositions, exhortations, and prophecies

contained in the Scriptures. If the Bible is truly a propositional expression

of God's will as well as the basis of faith and practice for the Christian,

human reason cannot be disregarded.

2. Rationalism: Human reason challenges,

undermines, and eventually destroys

religious

faith.

Rationalists maintain that human reason

Rationalists maintain that human reason

constitutes the foundational source of knowledge

constitutes the foundational source of knowledge

and truth, and therefore

provides the basis for

belief. Modern rationalism

rejects religious

authority and spiritual revelation as sources of

reliable information.

Beginning

with the humanistic revival of the European Renaissance (14th ‑ 16th

centuries), which extolled human creativity and potential, rationalism

flourished during the Enlightenment (18th century), with its systematic critique

of accepted doctrines and institutions. With time, rationalism branched out

into different varieties, such as empiricism (“Rely on your senses”), materialism

(“Only physical matter and laws can be trusted”), pragmatism (“Believe in what

works”), and existentialism (“Trust in your personal experience”). It

eventually evolved into modern skepticism which questions, doubts or disagrees

with generally accepted conclusions and beliefs and then further into atheism,

a denial of God’s existence. Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud are

representatives of this position.

In

its opposition to faith, rationalism argues that religions tend to support

traditional and sometimes irrational beliefs and to frustrate the

self-realization of human beings, both individually and collectively.

Rationalists also argue that there is no logical need for a First Cause in the

universe, and that the reality of evil in the world is incompatible with the

existence of a powerful, loving, and wise God as traditionally conceived by

Christians.

Most

institutions of higher learning offer an education based on a secular worldview

that rejects a priori transcendent reality and relies exclusively on human

observations and interpretations in their search for specialized knowledge.

3. Dualism: Faith and

reason are

3. Dualism: Faith and

reason are

autonomous and operate

in separate

autonomous and operate

in separate

spheres, neither

confirming nor

contradicting each other.

contradicting each other.

This position has been advocated by both

agnostic and Christian thinkers. The German

philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) said

that he was destroying the pretensions of human knowledge

in order to make room for faith. He claimed to have shown that all attempts to

establish the existence of God on the basis of rationalistic arguments were

doomed to failure. Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886‑1968) also rejected

rational or moral arguments that attempt to support theism or Christianity

because, in his view, those arguments presupposed their truth. For him, God is

magnificently revealed in Jesus Christ; human beings can only submit to this

revelation in faith, or reject it in sin. Belief cannot argue with unbelief, as

though there were relevant premises accepted by both; it can only preach to

it.

Many

contemporary scientists, some of them Christian, assume a more

radical stance. They maintain

that science deals with objective "facts," while religion addresses

moral issues from a personal, subjective perspective. Therefore, the spheres of

activity of reason and faith, knowledge and values, are unrelated to each other.[8]

Bible‑believing

Christians are not willing to accept this dualistic position. They argue, for

example, that Jesus Christ as portrayed in the Gospels is not only the center

of their faith as God incarnate, but also a real Person who lived on this earth

at a particular time and place in human history. They contend that the events

narrated and the characters presented in the Scriptures were also real and part

of the historical continuum, as evidenced by a growing volume of documentary

and archaeological evidences.

Any

attempt to separate the spheres of reason and faith relegates the Christian

religion to the realm of personal feelings, individual subjectivity, and

ultimately to the level of fanciful and irrelevant myth. Both Christians and

non‑Christians hold to varying and frequently contradictory beliefs. If

these cannot be distinguished as to their truthfulness or falsehood by the use

of reasonable evidence and argument, then no belief whether religious or

philosophical can claim reliability and allegiance.

4.

Synergy: Anchored in God’s revelation,

human reason can strengthen the human

quest for and commitment to truth.

Proponents

of this position maintain that

Proponents

of this position maintain that

Biblical Christianity

constitutes an integrated

and internally consistent

system of belief and

practice that deserves both

faith commitment

and rational assent.

The

realms of faith and reason overlap. Truths of faith alone are those revealed by

God but not discoverable by human reason (for example, the Trinity or salvation

by grace through faith). Truths to which we arrive through both faith and

reason are revealed by God but also discoverable and understandable by human

reason guided by the Holy Spirit (for example, the existence of God or the

objective moral law). Truths ascertained by reason and not by faith are those

not directly revealed by God but discovered by human reason (for example,

physical laws or mathematical formulas).[9]

C.

S. Lewis, the renowned Christian apologist, argued that in order to be truly

moral, human beings must believe that basic moral principles are not dependent

on human conventions. Those concepts possess a transcendent reality that makes

them knowable by all humans. [10] Lewis further maintained that the existence

of such principles presupposes the existence of a Being both entitled to

promulgate them and likely to do so.

If

the real world can be comprehended by human reason on the basis of

investigation and experience, it is then an intelligible world. The amenability

of this world to scientific inquiry both at the cellular and galactic levels

allows human beings to discover the laws that provide evidence for intelligent

design of the most intricate kind. This extremely elaborate design of all

facets of the universe, which makes possible intelligent life on this planet,

speaks of a Designer.

Therefore,

religious experience and moral conscience can be seen as signs of the existence

of the same Being that scientific research envisions as the intelligent

Designer of the cosmos and the Sustainer of life.

Reason,

then, can help us move from understanding to acceptance and, ideally, to

belief. But faith is a choice of the will, a decision to rely on God’s

revelation as foundational. Careful thinking, under the Holy Spirit's guidance,

may remove obstacles on the way to faith; and once faith is already present,

reason may strengthen religious commitment.[11]

Faith and reason in biblical perspective

The

Hebrew worldview, as reflected in the Old Testament, conceived of human life as

an integrated unit that included belief and behavior, trust and thought. During

most of their existence, the people of Israel accepted as fact the reality of God, whose

revelations were documented in their Scriptures and whose supernatural

interventions were evident in their history. For them, the enemy of belief in

the true God was not unbelief but the worship of pagan deities, mere products

of misguided human reason. Their goal was not theoretical knowledge but

wisdom--the gift of right thinking that leads to right choosing and right

living. "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom, and knowledge of

the Holy One is understanding" (Proverbs 9:10).

The

New Testament reflects the transition toward a different cultural context, in

which Hebrew monotheism had already become fragmented into various Jewish

sects, and had also been influenced by Greco‑Roman polytheism, emperor

worship, and agnosticism. As the early Christian Church interacted with this

religio-philosophical environment, it began to articulate the distinction

between faith and reason, granting to faith the position of privilege in the

life of the believer.

Bible

teaching with respect to faith and reason may be summarized

in the following

propositions:

$

The Holy

Spirit both awakens faith and illumines reason

If

it were not for the persistent influence of the Holy Spirit on human

consciousness, no one would ever become a Christian. In our natural condition

we do not seek God (Romans 3:10,

11), acknowledge our desperate need of His grace (John 16:7‑11), or

understand spiritual things (1 Corinthians 2:14). Only through the agency of the Holy Spirit we are

drawn to accept, believe, and trust in God (John 16:14). Once this miraculous transformation has occurred

(Romans 12:1, 2), the Holy Spirit teaches us (John 14:26), guides us "into all truth" (John 16:13), and allows us to discern error from falsehood (1

John 4:1‑3).

$ Faith must be exercised and developed

all through life

Each

human being has been given "a measure of faith" (Romans 12:4)Cthat is, the capacity to trust in GodCand each Christian is encouraged to grow "more

and more" in faith (2 Thessalonians 1:3). In fact, "without faith it

is impossible to please God, because anyone who comes to him must believe that

he exists and that he rewards those who earnestly seek him" (Hebrews

11:6). Hence the plea of an anguished father to Jesus, "I do believe; help

me overcome my unbelief!" (Mark 9:24)

and the insistent request of the disciples, "Increase our faith!"

(Luke 17:5). We grow in faith when, in response to God’s mercy toward us, we

increasingly trust in Him and obey his commandments.

$

God values and

appeals to human reason

Although

God's thoughts are infinitely higher than ours (Isaiah 55:8, 9), He has chosen

to communicate intelligibly with humankind, revealing Himself through the

Scriptures (2 Peter 1: 20,

21), through Jesus Christ who called Himself "the truth" (John 14:6;

Hebrews 11:1, 2), and through nature (Psalm 19:1). Jesus frequently engaged His

listeners in dialogue and reflection, asking for a thoughtful; response (see,

for example, His conversation with Nicodemus, in John 3, and with the Samaritan

woman, in John 4). At the request of the Ethiopian official, Philip explained a

Messianic prophecy found in Scripture so that he might understand and believe

(Acts 8:30‑35). The believers in Berea were praised because they "examined the

Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true" (Acts 17:11). The ultimate goal of life is to know God and to

accept Christ as Savior; such personal knowledge leads to eternal life (John

17:3).

$

God provides

sufficient evidence to believe and trust in Him

The

unbiased observer can perceive in the natural universe a display of God's

creative and sustaining power (Isaiah 40:26). God's "invisible qualitiesChis eternal power and divine natureChave been clearly seen" and understood by

"what he has made." Those who, in spite of the evidence, stubbornly

deny His existence and creative power "are without excuse" (Romans 1:20). Significantly, however, when Thomas expressed

doubts about the reality of Christ's resurrection, Christ provided the physical

evidence and challenged him to "stop doubting and believe" (John

20:27‑29). When we are confronted with questions regarding the origin of

the universe, our point of departure should be that of faith: "By faith we

understand that the universe was formed at God's command, so that what is seen

was not made out of what was visible" (Hebrews 11:3). [13]

$

God offers

clear guidance for life, but accepts the choices we make

In

the Garden of Eden, God gave Adam and Eve the option to obey or disobey Him,

and warned them of the terrible consequences of choosing the latter (Genesis 2:16, 17). Speaking through Moses, God reiterated the

options: "I set before you today life and prosperity, death and

destruction. . . . Now choose life, so that you and your children may

live" (Deuteronomy 30:15, 19). His appeals to human conscience are

exquisitely courteous: "Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If

anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and

he with me" (Revelation 3:20).

Above all, God seeks from His creatures love, obedience, and worship that are

freely considered and chosen (John 4:23,

24; 14:15; Romans 12:1 [logikén = reasonable and

spiritual]).

$

Faith and

reason can work together in the believer's life and witness

When

Jesus was asked to provide a summary of God's law, He stated that the first

commandment included, "Love the Lord your God. . . with all your

mind" (Mark 12:30; compare with

Deuteronomy 6:4, 5). Paul stated that the acceptance of Christ as Savior

depended on a thoughtful understanding of the gospel: "Faith comes from

hearing the message, and the message is heard through the word of Christ"

(Romans 10:17). Christians are expected to be "always prepared

to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that

you have" (1 Peter 3:15

[answer =apologían in Greek, defense, justification; reason = lógon

in Greek, a word, an explanation]). Peter also encourages Christians to

"make every effort to add to your faith goodness; and to goodness,

knowledge" (2 Peter 1:5, 6).

Dealing with questions and doubts

Thus

far, we have approached the subject of faith, reason, and choice from

philosophical and biblical perspectives. The range of options examined can be

diagramed as follows:

Unbelief Faith

Doubt Belief

Questions

& Choice

Let

us now look at the practical implications of what we have examined. How should

Bible‑believing Christians deal with the tension that inevitably arises

between their faith and their reason when they face conflicting issues in their

study, research, or life experience? The following suggestions can help:[14]

1.

Remember that God and truth are synonymous. God created us as inquisitive creatures. He is honored when we

exercise our mental abilities to explore, discover, learn, and invent as we

interact with the world that He created and sustains. When we use our

rationality and creativity in an attitude of humility and gratitude, we are

loving God with our mind. Believers should not be afraid of study, research,

and discoveries. If there are discrepancies between "God's truth" and

"human truth," it is because we misunderstand one or both. Since in

Christ "are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge"

(Colossians 2:3), all truth is God's truth.

2.

Accept that the Bible does not tell us everything there is to know. God's

knowledge is infinitely broader and deeper than ours: “As the heavens are

higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts

than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:9). For that reason, He had to condescend in

order to establish communication with us, within our ability to comprehend. As

Jesus told the disciples, "I have much more to say to you, more than you

can now bear" (John 16:12).

In addition, our human fallenness clouds and limits our understanding.

"Now we see but a poor reflection; then we shall see face to face. Now I

know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known" (1

Corinthians 13:12).The Bible can be approached as a book of history or

literature or laws or biography. But its main purpose is to help us know God

and to teach us how to become friends with Him and live godly lives now in

preparation for eternity. In the New Earth we will have the time and the

opportunity to explore and learn from the vast complexity of the cosmos and its

inhabitants.

3.

Distinguish between God's Word and human interpretations. Human traditions and preconceived ideas frequently

make us read things into the Bible that are not there. The case of Copernicus

(1473‑1543) offers a sobering example.

On the basis of his study and observations, this astronomer proposed

that the planets, including the Earth, revolved around the Sun. Since most

astronomers still accepted Ptolomy's geocentric theory, many religious leaders

of that time considered Copernicus' ideas heretical. They believed that because

of the importance of human beings and the centrality of this Earth in God's

plans, the Sun and planets must revolve around the Earth. When Galileo and

Kepler provided evidence in favor of Copernicus's views, the discovery did not

destroy God or Christianity.

Three

centuries later, Charles Darwin argued against many theologians of his time who

believed in the absolute fixity of the species, which is not required by the

Bible narrative. Not many years ago, some Christians stated that God would not

allow humans to travel in space or land on the Moon. Again, those statements

were proven wrong, showing they were based on personal interpretations and

extrapolations.

4.

Realize that the scientific enterprise is an ongoing exploration. Experimental science deals only with phenomena that

can be observed, measured, manipulated, repeated, and falsified. Contrary to

the impression that one gains from many science textbooks and the popular

media, experimental science frequently leads to adjustments and even reversals.

True, many of the basic laws are now universally accepted. But as scientists

continue their research, theories and explanations that were accepted for years

are replaced by other theories and interpretations that seem more accurate and

reliable.[15] As a matter of method, scientists work in their disciplines

within a naturalistic framework, which excludes the supernatural. Many of them

are agnostics or atheists; however, their beliefs are not based on scientific

evidence but on personal choice. Only when we approach the natural world from

the perspective of God’s revelation in Scripture, we begin to understand it

correctly. Scientists and researchers who are open to the possibility that God

exists, find abundant evidence in the natural world to indicate that there is

an Intelligent Designer who planned and sustains the universe and life.

5.

Create a mental file for unresolved issues. Some questions will inevitably arise in our studies, in our life

experience, and even in the Bible for which we don't have satisfactory answers.

In some cases, we find an explanation later. In other cases, questions remain

unresolved. A classic example is the tension between our belief in an all‑powerful,

loving God and the suffering of the innocent. Although there are abundant

evidences of God's power and care, we cannot fully understand why human

tragedies and natural disasters occur in a universe in which He is sovereign.

The biblical concept of a cosmic conflict between God and Satan that involves

this planet and its inhabitants provides a useful framework for understanding

this and other deep mysteries. In the meantime, the best approach is to suspend

judgment, keep studying them prayerfully, and seek the counsel of mature

believers. Some day we will gain a new insight or God will make these contradictions

clear to us. Faith in God and recognition of our own finitude demand that we

learn to live with some uncertainties and mysteries.

Conclusion

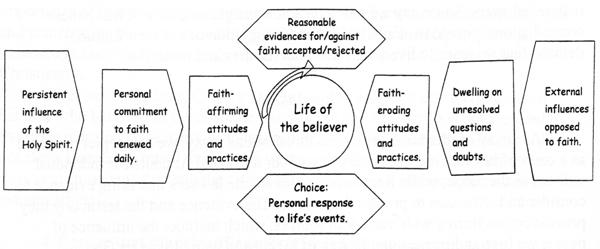

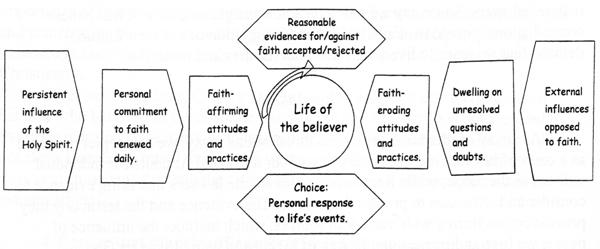

As a

way of illustrating the main thrust of this essay, we can depict our mind as a

court of law that operates every day of our lives.[16] At court our individual

will sits as the judge, while Reason and Faith are the lawyers that bring

evidence to consider and witnesses to present their views. The evidence and the

testimony they provide comes from a wide variety of sources, which include: the

influence of people we love and respect, the feeling of loving and being loved

by God and others, our social interaction and dialogue with others, the

messages of the Bible, observations of the natural world, spiritual experiences

in prayer and service, study and research, the joys and sorrows of life,

individual and collective worship, our response to beauty in the arts, the

effect of our habits and lifestyle, and the search for inner consistency and

authenticity.

Our

will daily sifts through this multiplicity of emotional, spiritual, rational,

and aesthetic perceptions and data, comparing them with the CodeCour worldview.[17]

At

times the arguments advanced are accepted and strengthen our faith convictions.

At other times, the evidence presented trigger an adjustment in our worldview

and a modification of our beliefs. These changes, in turn, have an impact on

our conduct. Other times, the will prefers not to decide.

Sitting

respectfully in the background, the Holy Spirit is always ready to speak a word

of caution, correction, or affirmation. Other voices, perhaps those of

uninvited and hostile observers, are also heard in the courtroom, raising

objections, presenting contrary evidence, and insinuating doubts. The court of

our will continues to deliberate until the very last day of our conscious life.

This

permanent interaction between faith, reason, and choice in the life of the

believer may be outlined as follows:

As

thoughtful Christians, we are called to love God with both our mind and our

will, integrating in our life the demands of faith and intellect. For the

educated believer there is "no incompatibility between vital faith and

deep, disciplined, wide‑ranging learning, between piety and hard

thinking, between the life of faith and the life of the mind."[18] In

order to strengthen these three facets of our God‑given mental abilitiesCfaith, intellect, and willCwe must deepen daily our friendship with Jesus, our

study of the Scriptures, and our commitment to truth as revealed by God.[19] He

trusts that, in view of the evidence available to us, we will be intelligent

decision‑makers.

How,

then, do we love God with all our mind? By being

·

Thankful to

Him for our mental abilities, opportunities, and blessings

·

Humble and

teachable on how to use our reason, imagination, and influence

·

Responsible

in applying our discoveries, in treating others, and in relating to the natural

world that God has entrusted to us

·

Available to

communicate the Good News, help others, and honor Him in everything we think,

say, and do.

________________________________________________________________

Postlude with two parables

Is there a gardener?

Once

upon a time two explorers came upon a clearing in the jungle. In the clearing

growing side by side there were many flowers and also many weeds. One

of the explorers exclaimed,

"There must be a gardener tending this plot!" So they pitched their

tents and set a watch.

But

though they waited several days no gardener was seen.

"Perhaps

he is an invisible gardener!" they thought. So they set up a barbed-wire

fence and connected it to electricity. They even patrolled the garden with

bloodhounds, for they remembered that H. G. Wells's AInvisible Man" could be both smelled and touched

though he could not be seen. But no sounds ever suggested that someone had

received an electric shock. No movements of the wire ever betrayed an invisible

climber. The bloodhounds never alerted them to the presence of any other in the

garden than themselves. Yet, still the believer between them was convinced that

there was indeed a gardener.

"There

must be a gardener, invisible, intangible, insensible to electric shocks, a

gardener who has no scent and makes no sound, a gardener who comes secretly to

look after the garden that he loves."

At

last the skeptical explorer despaired, "But what remains of your original

assertion? Just how does what you call an invisible, intangible, eternally

elusive gardener differ from an imaginary gardener or even from no gardener at

all?"[20]

The invisible gardener

Once

upon a time, two explorers came upon a clearing in the jungle. A man was there,

pulling weeds, applying fertilizer, and trimming branches. The man turned to

the explorers and introduced himself as the royal gardener. One explorer shook

his hand and exchanged pleasantries. The other ignored the gardener and turned

away.

"There

can be no gardener in this part of the jungle," he said. "This must

be some trick. Someone is trying to discredit our secret findings."

They

pitched camp. And every day the gardener arrived to tend the garden. Soon it

was bursting with perfectly arranged blooms. But the skeptical explorer

insisted, "He's only doing it because we are hereCto fool us into thinking that this is a royal

garden."

One

day the gardener took them to the royal palace and introduced the explorers to

a score of officials who verified the gardener's status. Then the skeptic tried

a last resort, "Our senses are deceiving us. There is no gardener, no

blooms, no palace, and no officials. It's all a hoax!"

Finally

the believing explorer despaired, "But what remains of your original

assertion? Just how does this mirage

differ from a real gardener?"[21]

. . . . . . .

Notes and references

*Unless

otherwise noted, all Bible passages in this essay are quoted from the New

International Version.

1.

Martin Luther, Table Talk, chapter

353 (1566). Luther had earlier distinguished between the ministerial and the magisterial

uses of reason. In its ministerial role, reason submits and serves the gospel,

helping Christians to better understand and explain their faith. In its

magisterial role, reason stands over and above the gospel and pretends to judge

it on the basis of argument and evidence.

2.

Ellen G. White, Education (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1952),

p. 17.

3.

Ibid.

4.

In the same book Education, Ellen G.

White defines this virtue crisply: "Faith is trusting God, believing that

He loves us and knows best what is for our good" (p. 253).

5.

"You believe that there is one God. Good! Even the demons believe that and

shudder" (James 2:19).

6.

“This is what the Lord says:… ‘Let him who boasts boast about this: that he

understands and knows me, that I am the Lord, who exercises kindness, justice

and righteousness on earth, for in these I delight,’ declares the Lord”

(Jeremiah 9:25). “This is eternal life: that they may know you, the

only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

7.

See Hugo A. Meynell, "Faith and Reason" in The Encyclopedia of

Modern Christian Thought, edited by Alister E. McGrath (Oxford: Blackwell,

1993), pp. 214‑219.

8.

Stephen Jay Gould who, until his recent death, taught the history of science at

Harvard University, stated that “the supposed conflict between science

and religion… exists only in people’s minds and social postures, not in the

logic or proper utility of these entirely different, and equally vital

subjects.” In his view, “science tries to document the factual character of the

natural world, and to develop theories that coordinate and explain these facts.

Religion, on the other hand, operates in the equally important, but utterly

different, realm of human purposes, meanings, and values” (Rock of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life [Westminster, Maryland: Ballentine, 1999], pp. 3, 4.

9.

Centuries ago, Thomas Aquinas (1225‑1274) proposed a rational foundation

for the Christian faith and its teachings in a monumental philosophical and

theological treatise, the Summa Theologica. Aquinas claimed, for

example, that the existence of God and the immortality of the soul could be

shown on the basis of general rational principles alone, while such doctrines

as the Trinity and the Incarnation had to be accepted on divine revelation and

authority. With his reliance on the authority of early Christian authors and on

Aristotle and his commentators, Aquinas represents the culmination of medieval

scholasticism. Christians in the Protestant tradition object to Aquinas's

excessive trust in philosophical argumentation and human rationality, and

propose instead the primacy of the Scriptures (Sola Scriptura) as the single source of Christian belief and

practice.

10.

The Apostle Paul argues thus: “Indeed, when Gentiles, who do not have the law,

do by nature things required by the law, they are a law themselves, even though

they do no have the law, since they show that the requirements of the law are

written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness and their

thoughts now accusing, now even defending them” (Romans 2:14, 15).

11.

See Peter Kreeft and Ronald K. Tacelli, Handbook of Christian Apologetics

(Downer's Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1994), pp. 29‑44. See also

Richard Rice, Reason and the Contours of

Faith (Riverside, California: La Sierra University Press, 1991).

12.

Stephen Dunn, New & Selected Poems,

1974-1994 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994), pp. 183, 184.

13.

"God never asks us to believe, without giving sufficient evidence upon

which to base our faith. His existence, His character, the truthfulness of His

word, are all established by testimony that appeals to our reason; and this

testimony is abundant. Yet God has never removed the possibility of doubt. Our

faith must rest upon evidence, not demonstration. Those who wish to doubt will

have opportunity; while those who really

desire to know the truth will

find plenty of evidence on which to rest their faith" (Ellen G. White, Steps

to Christ [Mountain View, California: Pacific Press, n.d.], p. 105).

14.

Adapted from Jay Kesler, "A Survival Kit," College and University

Dialogue 6:2 (1994), pp. 24, 25.

15.

Thomas Kuhn, in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University

of Chicago Press, 1970) showed how scientists work within a mutually accepted

conceptual paradigm that changes with time. Ian Barbour stated: “Science does

not lead to certainty. Its conclusions are always incomplete, tentative and

subject to revision” (Religion in an Age

of Science [1990], vol. 1, p. 35). Christian apologist C. S. Lewis caution should

be heeded: "Science is in continual change, and we must try to keep

abreast of it. For the same reason, we must be very cautious of snatching at

any scientific theory which, for the moment, seems to be in our favour. We may

mention such things, but we must mention them lightly and without claiming that

they are more than interesting. Sentences beginning >Science has now proved= should

be avoided. If we try and base our apologetic on some recent development in

science, we shall usually find that just as we have put the finishing touches

to our argument, science has changed its mind and quietly withdrawn the theory

we have been using as our foundation stone" ("Christian

Apologetics," 1945).

16.

I am indebted to Michael Pearson for the basic structure of this illustration,

which I have elaborated here. See his essay, "Faith, Reason, and

Vulnerability," College and University Dialogue 1:1 (1989), pp. 11‑13,

27.

17.

A worldview is a global outlook on life and the world that each mature

individual possesses. Worldviews answer four basic questions: Who am I? Where

am I? What is wrong? What is the solution? See Brian Walsh and Richard Middleton,

The Transforming Vision: Shaping a Christian Worldview (Downers Grove,

Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1984).

18.

Arthur F. Holmes, Building the Christian Academy (Grand

Rapids,

Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2001), p. 5.

19.

Too many Christians ignore the important role of reason in developing a mature

faith. “Our churches are filled with Christians who are idling in intellectual

neutral. As Christians, their minds are going to waste. One result of this is

an immature, superficial faith. People who simply ride the roller coaster of

emotional experience are cheating themselves out of a deeper and richer

Christian faith by neglecting the intellectual side of that faith. They know

little of the riches of deep understanding

of Christian truth, of the confidence inspired by the discovery that

one’s life is logical and fits the facts of experience, of the stability

brought to one’s life by the conviction that one’s faith is objectively true”

(William Lane Craig, Reasonable Faith:

Christian Truth and Apologetics, revised

edition [Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1994], p. xiv.

20. Anthony

Flew and John Wisdom, "Theology and Falsification," in John Hick,

ed., The Existence of God (New York: Collier Books, 1964), p. 225.

21.

John Frame, "God and Biblical Language: Transcendence and Immanence,"

in John W. Montgomery, ed., God's Inerrant Word (Minneapolis: Bethany

Fellowship), p. 171.

- - - - - - -

![]()

the role of

reason in arriving at truth.

the role of

reason in arriving at truth.