Institute for Christian

Teaching

Education Department of

Seventh-day Adventists

THE USE OF HUMAN

SUBJECTS IN RESEARCH AT ADVENTIST COLLEGES

AND UNIVERSITIES: SUGGESTED

GUIDELINES

by

Beverly J. Rumble

Editor, Journal of

Adventist Education

General Conference of

Seventh-day Adventists

Silver Spring, Maryland

Prepared for the

International Faith and

Learning Seminar

held at

Newbold College, Bracknell,

Berkshire, England

June 1994

207-94 Institute for

Christian Teaching

12501 Old Columbia Pike

Silver Spring, MD 20904 USA

The term "human experimentation" often

brings to mind horrifying abuses of human rights, such as experiments in Nazi

concentration camps. Other, less famous

examples include the following:

In the late

1800s E. Franenkel inoculated the eyes of terminally ill infants with gonorrhea

cultures.[1]

Early in the 20th

century Richard P. Strong (later professor of tropical medicine at Harvard)

injected plague germs into death-row inmates in the Philippines.[2]

In the Tuskegee

(Alabama) syphilis experiment that stretched over 40 years, researchers

withheld treatment from 399 poor black men so that they could study the

physical effects of untreated venereal disease.[3]

In 1966, Henry

Beecher, a Harvard Medical School professor, exposed more recent abuses in

human experimentation. His "roll

of dishonor" included withholding of penicillin from uninformed servicemen

with streptococcal infections, a number of whom contracted rheumatic fever;

feeding of live hepatitis viruses to residents of a state institution for the

retarded to study the disease and attempt to develop a vaccine; the injection

of live cancer cells into elderly and senile hospitalized patients without

telling them the nature of the cells; and a number of other shocking abuses.

Beecher maintained that "unethical or questionably ethical procedures are

not uncommon" among researchers, and that the rights of human subjects

were widely disregarded.[4]

In order to

investigate whether side effects such as nervousness and depression could be

caused by oral contraceptives, Goldzieher gave dummy pills to 76 women who

sought treatment in a San Antonio, Texas, clinic to prevent further

pregnancies. None of the women was told

that she was participating in research or receiving placebos. Most of the

experimental subjects were poor Mexican-Americans with several children.[5]

In at least 31

separate experiments between the mid-1940s and the 1970s the U.S. Government

exposed nearly 700 people to radioactive substances. These included an

experiment in which Manhattan Project scientists, the designers of the first

atomic bomb, injected 18 people with "relatively massive quantities of

bomb-grade plutonium" to see how much of the toxic substance their bodies

would retain.[6]

The above examples highlight abuses in medical

experiment. But some investigations by

social scientists have been scarcely less questionable. For example:

Zillman and

Bryant randomly assigned 80 male and female undergraduates to watch various

amounts of heterosexual pornography of a six-week period. The students were

then asked to estimate the percentage of U.S. adults performing certain sexual

acts, and to recommend a prison term for a rapist described in a newspaper

article.[7]

To evaluate a

questionnaire that proported to test peoples' comprehension of moral

principles, a team of social scientists proposed to administer it to teenagers

at a male juvenile delinquency rehabilitation center, and then tempt them to

lie or steal.[8]

Posing as

fellow believers, researchers covertly studied a small flying saucer cult whose

members were waiting for the end of the world. The ratio of

researcher-believers was so high, however, that their participation wronged

those studied not only by lying to them but also by providing false

"evidence" to reinforce their beliefs (and at the same time, altering

the phenomena under investigation).[9]

Other

studies have attempted to find a genetic link to criminal behavior or

intelligence,[10] or have

exposed subjects to psychoactive drugs without their knowledge.

Professors and students at

Seventh-day Adventist healthcare training institutions, as well as at our other

colleges and universities sometimes conduct medical and social science

experiments and studies using human subjects.

In the United States, the federal government closely regulates medical

experimentation on humans; therefore, that area will not be the primary focus

of this paper, though some of the policies established for healthcare

institutions provide the basis of its suggestions for social science research.

Administrators would be well advised to use these guidelines in developing

policies for their institutions. A list

of helpful sources is included at the end of the paper.

Reasons of Experimenting on Human Subjects

As abhorrent as the above

experiments seem to us today, they appeared perfectly defensible and even

urgently necessary to the people who performed them. So we are forced to look

more closely at the reasons for using human beings in research.

In general, researchers

argue that hey are contributing to and extending human knowledge through

research, and that their studies advance health, science, and human welfare

(perhaps also providing the researchers with some renown in the annals of

science). An ethicist cementing on such

research said that these scientists seek to avoid the "menace of avoidable

ignorance."[11] In times of

national emergency, such as wartime, research seems a patriotic imperative, for

it provides knowledge that may help subdue enemy aggression or save the lives

of military personnel.

Researchers claim that they

need to use human subjects in their studies because they cannot achieve the

same results with simulations or animals. This is especially true in social

science research. In resisting external

controls on their research, they argue that freedom of inquiry is essential for

healthy research.[12]

Despite researchers'

commitment to the general good and to extending human knowledge, their

"omnivorous appetite"[13]

for scientific research, as ethicist Paul Ramsey puts it, can cause them to

lose sight of the importance of each individual subject. As Henry Beecher

pointed out.

"Any classification of human experimentation as

'for the good of society' is to be viewed with distaste, even alarm.

Undoubtedly all sound work has this as its ultimate aim, but such high-flown

expressions. . . have been used within recent memory as cover for outrageous

acts. . . There is no justification. . .for risking an injury for the benefit

of other people. . .such a rule would open the door wide to perversions of

practice, even such as were inflicted by Nazi doctors on concentration camp

prisoners. . .The individual must not be subordinated to the community."[14]

Although progress depends

heavily on science and technology, we no longer naively assume that this is the

way to the good life. Nuclear weapon,

widespread pollution and abuses of human beings in research like that cited

above have sensitized us to the potential for evilas well as goodthat science

and technology can achieve. Previously

undreamed-of capabilities for human beings to control birth and death, to

transplant human organs, even to manipulate genetic material, have highlighted

the need for external controls over researchers and medical personnel.

Exposes in scientific

journals and the popular press have revealed a stark conflict of interest

between researchers' ambitions and subjects' well being. As a result, in the U.S. federal regulations

have been passed requiring oversight and collective decision making.[15]

The areas that have

generated the most serious ethical problems are the design of the experiment,

choice of subjects, obtaining informed consent, balancing risk to the subject

with benefits to the researcher and society, and maintaining the participant's

dignity and privacy. These topics will be dealt with in greater detail later in

this paper.

Moral Implications

As Christians, we view the

scientific method differently from those who hold a naturalistic philosophy

about the origins of human beings. We believe that God designed the universe to

operate in an orderly way, although He may occasionally step outside of natural

processes to perform miracles.

Therefore, since the universe is orderly, and God made human beings

capable of rational thought, we can design experiments to explore the

mechanisms of the physical universe and even to study human behavior through

the social sciences. We can thereby discover some of the marvelous aspects of

God's creation, extend the boundaries of knowledge, and alleviate human

suffering.

However, our beliefs will

put certain constraints on the kinds of scientific research that we do. For

example, if we believe that human beings are created in the image of God, we

will treat humanity at every stage of life with respecteven miscarried

fetuses, human tissue, and frozen embryosin contrast to how we would act if we

believed that homo-sapiens are essentially no different from other creatures in

the natural world.

Human experimentation raises

a number of religious and ethical dilemmas.

Traditionally, such research occurred in the field of medicine, where

the physician was expected to be committed to the good of the individual

patient. The primary rule of medical morality was to do no harmbased on the

Hippocratic Oath and guidelines for medical ethics drawn up by the General

Assembly of the World Medical Association in 1949.[16]

The timing of the latter guidelines was doubtless inspired in part by the

Nuremberb trials, which revealed the flagrant abuses of Nazi researchers.

How do we balance the needs

of the individual with those of society? Should researchers be allowed to

induce or coerce individuals to subject themselves to certain risks for the

good of others? To clarify this, let us look at two extreme positions: The

first would subordinate the individual to the good of society. This would allow

medical and psychological experimentation on human beings without their consent

if the studies would benefit society. This represents the classical utilitarian

theory of choosing the greatest good for the greatest number. Thus, anytime a

researcher could claim that a procedure or experiment would benefit society, he

or she could justify overriding the rights of the individuals involved for each

person counts for only one.

At the opposite extreme,

absolute individualism acknowledges no significant relationship between the

individual and society, and asserts the primacy of the individual over the

group. Most ethicist acknowledge that at times the individual must be limited

by the needs of society, and that each person has an obligation, as part of a

community, to act in ways that benefit others.

Human beings do not exist as isolated atoms. They

are actually constituted by their relationshipsto the world, to their family,

to their fellow human beings, to the Church, and to God. It is important to

stress that these relationships are not extrinsic or spatial but intrinsic;

they belong to the very fabric of each person's being.[17]

Jesus' admonition to

"love your neighbor as yourself" ties together both respect for

persons and one's obligation to the larger community.

It may be helpful at this

point to divide moral obligations into two categoriesthose that are required

of all human beings, and others that are heroicabove and beyond the call of

duty. Some people would want to volunteer for experiments to help others,

despite the risk to themselves. But no one should be coerced into participating

in such studies. In every case, we must evaluate the balance between the risks

and potential benefits and give potential subjects enough information to allow

them to make an informed choice.

In recent times, Western

society has become more concerned about protecting the individual against

possible invasions of dignity, privacy, and freedom. Christian ethics has

always asserted that every person possesses certain inalienable rights, that

individuals are ends in themselves. They are never to be used merely as a means

to something elseno matter what their race or color, how well or poorly

endowed with talents, or how primitive or developed. Therefore, the individual

takes primacy over society. However much the good of the whole exceeds that of

any of its parts, and whatever duties each person owes to society, individuals

constitute the supreme value, and society exists only to promote the good of

its members.

"In view of people's

tendency to exploit their fellow human beings, the scriptural revelation of the

innate, inalienable dignity and value of the individual provides an indispensable

bulwark of freedom and growth."[18]

Christ's example and teachings and the admonitions of Old Testament prophets

provide a basis ethical framework for making decisions about how to treat

people, both in daily life and in experimentation.

Our Lord has taught us that the Decalogue is

centrally a statement of what love demands. But since justice is one of the

things that love enjoins, it is possible to distill from the Ten Commandments a

list, even though it be a partial list, of the rights and liberties men can

claim. . . This. . is only a partial list of the rights we tend to claim. . .

We can go to the Old Testament prophets and learn from, say, Hosea, that the

powerless have a right to be protected against the strong.[19]

Each human being is unique,

created in the image of God and redeemed at an infinite price. He or she

possesses the power to think and to do, according to Ellen White.[20]

This means that God places a high value on allowing each person to choose

freely what actions he or she will take. This principle should influence

researchers' choice of subjects and topics for investigation. They too are free to choose, but should keep

in mind Paul's admonition: "Brethren, ye have been called unto liberty;

only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one

another" (Galatians 5:13).

Research, optimally, should

consist of a "truly joint venture between two human beings working

together for the increase of human knowledge and the ability of human beings to

serve one another. From this perspective, the subject is a coparticipant in the

human quest for progress."[21]

This gives the subject a more active role, and requires the researcher to

respect his or her humanity and rights as a freewill agent. Therefore, as Hans

Jonas points out, the most highly motivated, the most highly educated, and the

least captive members of our communities would make the best research subjects.

Subjects with poorer knowledge, motivation, and decision-making freedoms (who

are consequently more readily available in terms of number and possible

manipulation) should be used more sparingly and reluctantly.[22]

Curran suggests as a criterion whether one would subject his or her own

children to the proposed experiments.[23]

Unfortunately, this has not been the usual method of choosing subjects

for experimentation. Those from lower socioeconomic classes, minorities,

prisoners, the gullible, and the mentally incompetent have borne an undue share

of the burden as subjects of experimentation.

To treat individuals

ethically means not only to respect their decisions and protect them from harm,

but also to actively attempt to ensure their well-being. This is encompassed in

the term beneficence, which

implies the following principles for research on human beings: "(1) do not

harm, and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms."[24]

Although discovering what

will in fact benefit people may require exposing them to risk, forethought and

oversight are needed to assess when it is justified to seek certain benefits

despite the risks involved, and when the experiment should be forgone because

of the possible risks. Such risks may

involve psychological, physical, legal, social, or economic harm.

For the Christian

researcher, the principle of stewardship is also a relevant concern. "We

do not possess anything in the world, absolutely, not even our own [or other

people's] bodies; we hold things in trust for God, who created them, and are

bound, therefore, to use them only as He intends that they should be

used."[25]

Montemorelos University's

"Philosophy and Role of Research" statement expresses well the

concept of stewardship:

A consciousness of our stewardship of God's creation

prohibits the investment of time, ability, or economics resources in the search

of knowledge that may result in adverse effects for human life, or that involve

immoral elements or consequences. By the same token, this consciousness

motivates us to the diligent research of all practical possibilities toward the

common well-being of mankind.[26]

Christian principles should

be applied at every stage of researchplanning the study, choosing subjects,

informing participants of the risks and benefits, performing the experiment,

debriefing subjects, and guarding the privacy of subjectsas well as careful

analysis of the data, reporting of the study, and ethical use of the data after

the study has been completed.

Design of the Experiment of Study

David Rutstein points out

that "Attention must be given to the ways an experiment can be designed to

maintain its scientific validity, meet ethical requirements, and yet yield the

necessary new knowledge."[27]

The experiment's design goes straight to the basis questions asked by the

investigator. What problem does he or she seek to solve? What information does

he desire to obtain? Are the proposed methods and techniques consistent with

Christian ethics?

In the medical area, a

standard question is whether the experimentation is therapeutic, or conducted

only for its research value. Research is clearly non-therapeutic when it is

carried out solely to gain information that will benefit others, but which is

of no use to the patient.

An analysis of the design of

social science experiments should address the following questions:

Is it ethical

to ask people to perform the actions specified by the researcher?

Will the procedures

cause psychological injury or humiliation to the subjects?

Could any part

of the research cause irreversible changes in the subjects' personality or

moral values?

Do the

researcher's actions mislead subjects by lending support to false ideas or

prejudices?

Application of the principles underlying these

questions would clearly eliminate any proposals that require participants to

perform illegal or immoral acts, that expose them to pornography or depictions

of violence, or ask them to participate in psychological experiments that would

be demeaning to themselves or to others.

Potential conflicts of

interest and threats to researcher integrity also present ethical

dilemmas. Research sponsored by an

organization that expects a particular result (a tobacco company, for example),

whether or not it uses human subjects, should raise a red flag for researchers

who seek to do pure science and arrive at truth, unencumbered by any type of

coercion. Christian researchers will doubtless also want to engage in serious

reflection and prayer, perhaps seeking pastoral and ethical guidance, before

participating in research that may contribute to military weaponry or be used

to destroy or harm human beings or the natural world.

Choosing Subjects for Research

Methods for choosing

subjects may not be as obvious or ethically neutral as some researchers would

have us believe. Participant selection raises ethical issues on two levels:

social and individual. Researchers should not offer potentially beneficial research

only to certain categories of persons, or select only "undesirable"

persons for risky research. Social

justice requires that distinctions be drawn between classes of subjects. Those

who cannot give consent or who ought not to be further burdened, such as the

indigent, children, the institutionalized or mentally infirm, and prisoners

should be used only under certain carefully controlled conditions.

Conversely, a variety of

groups should be included in research, particularly if the anticipate benefits

of the studies might better their lives.

This would mean, for example, not testing drugs only on men, or

selecting only young, well-educated subjects for research on organ transplants.

Disclosure

Candor helps ensure the

integrity of the encounter between researcher and subject, and prevents the

researcher from exploiting and subordinating participants to the research

process. It demeans the subject's humanity to see him or her simply as a case

or a statistic, a mere representative of some class or category of persons.

As autonomous agents, human beings have the right to

control their own lives and to receive enough information to make informed

decision; therefore, researchers should share adequate facts to enable the

subjects to judge for themselves the balance between risk and benefit, and to

decide whether to participate in the study.

In general, the law imposes a strict duty of

disclosure, wherever an individual with a great deal to lose is exposed to a

risk or is asked to relinquish rights by someone with considerably greater

knowledge.[28]

Less than complete

disclosure deprives the subject of the opportunity to consciously and

deliberately render service in a crucial social enterprise, while greater

candor enables him or her to become a partner in the thrill of scientific

discovery and perhaps relief of human misery.

Therefore, each subject

should receive an explanation of the procedures to be followed and their

purpose, including (1) identification of any procedures that are experimental;

(2) a description of the discomforts and risks, as well as benefits that may

reasonably be expected; (3) disclosure of any appropriate alternative

procedures that might be advantageous; (4) an offer to explain any questions

about the procedures; (6) assurance that the subject is free to withdraw his or

her consent and to stop participating in the project at any time.[29]

Coercion

Subjects should participate

in research without coercion, after the risks and benefits of their

participation have been fully explained.

But there remains some question whether certain groups are capable of

making truly free choices, either because of their circumstances or the nature

of their relationship to the researchers.

If the explanations are

geared to their level of comprehension, even poorly educated persons can be

considered capable of participating freely in research. However, certain groups present ethical

difficulties because they cannot give informed consent or are susceptible to

coercion.

Payment for participation

may raise concern, if care is promised to indigent persons in exchange for

participating in experimentation, or if people "volunteer" for a

study because of financial need or their desire for some benefit, such as

reduced prison sentence.

Other who cannot give

consent, or who are incapable of understanding the nature of the proposed

experiment, constitute a particularly vulnerable group. This would include children, the underclass,

and the mentally incompetent.

Jesus' example is

instructive in this area. According to

Robert Mortimer, "The Son of God showed particular care and concern for

the fallen, the outcast, the weak and the despised."[30]

Likewise, researchers should treat with special regard those in vulnerable

groups.

John Fletcher, a Christian

ethicist who has devoted much study to the practical aspects of informed

consent, suggests that several other factors can affect the autonomy of

subjects: whether they are ill or dependent on the researcher for medical care,

the circumstances surrounding the institution, and the desire to please the

investigation.[31]

Psychological researchers

generally have less power over their subjects than their biomedical

counterparts. However, their experiments often occur within the context of a

university or other large institution, and invoke the more generalized prestige

of "science," which subjects may perceive as authoritative. For example, Milgram's famous studies[32]

testing the likelihood that people would obey the commands of a authority

figures, to the point of administering shocks to uncooperative subjects, took

place at Yale University and a New Haven research laboratory. Subjects would doubtless hold even higher

ethical expectations of a Christian institution. Consequently, the Christian

researcher might have greater moral authority and more effective powers of

persuasion with subjects from his or her religious tradition.

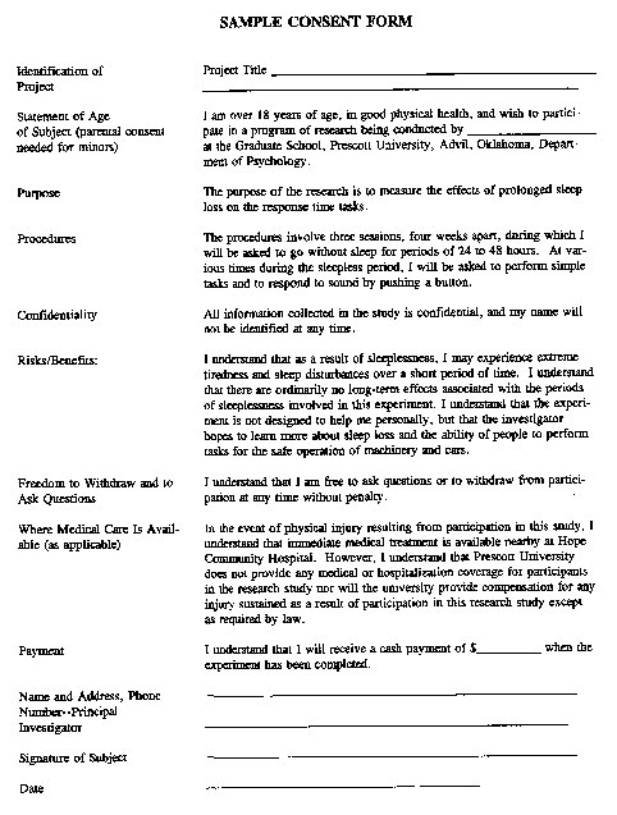

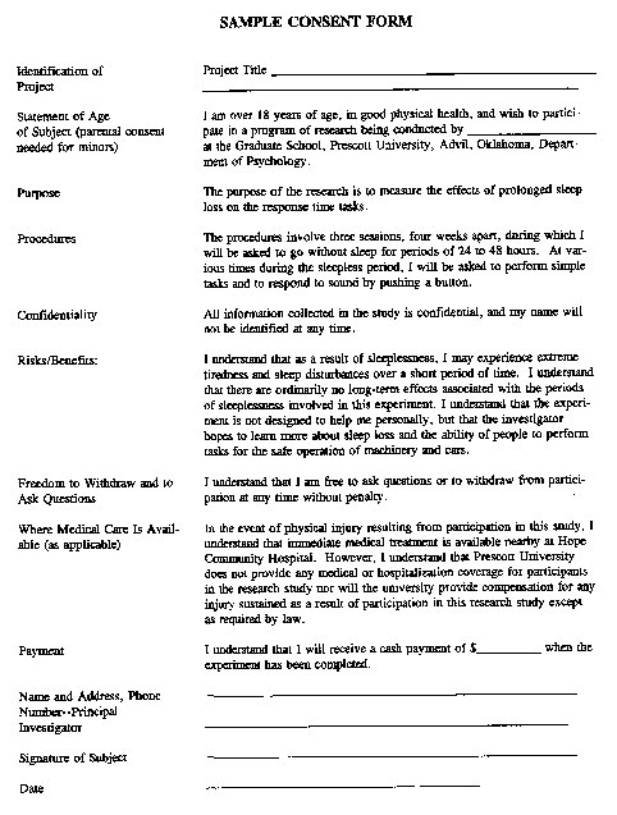

Informed Consent

Respect for person's demands

that, in most cases, subjects should enter into the research voluntarily and

with adequate information. They should receive the following information: the

research procedure; risks and anticipated benefits, if any; alternative

procedures (where therapy is involved); a statement inviting the subject to ask

questions; and an explicit statement allowing him or her to withdraw at any

time from the research. The details should be given in a way that the subject

can understand, allowing time for him or her to process the information and

return with additional questions. On occasion, it may be helpful to give some

sort of oral or written test of comprehension. (See the sample consent form in

Appendix B).

Deception

Many researchers argue that

the only way to obtain accurate information about certain aspects of their

subjects' behavior is not to inform them of the nature of the experiment or

study. If the subject knew his or her actions were being studied, this would

almost certainly result in the behavior being modified. Solutions to this problem have been

difficult to find. Simulations have proved inadequate, both methodologically

and ethically, since subjects who are asked to describe how they would react in

a particular situation may not know, or don't want to tell. On the other hand, if the simulations are

too realistic, they may cause stresses resembling those experienced by people

participating in the actual experiment.[33]

Deception appears to be

fairly widespread in various kinds of scientific research. In tests of

medicines and treatments, patientsand even doctorsare not told which persons

are in control groups or are receiving placebos. Likewise, deception occurs rather frequently in social science

studies. In 1978, Diener and Crandall estimate that between 19% and 44% of

social psychology and personality research involved direct lying, and one study

of psychology experiments suggested that complete information was given in only

3% of the cases reviewed.[34]

The category of subjects

being used may affect the prevalence of deceptive practices. Researchers may be

tempted to treat more cavalierly a disadvantaged group, feeling that they

cannot seriously disrupt the research, compared to more powerful or well-educated

subjects.

Deception always poses the

potential for harm to those being deceived, since they might have chosen to

avoid participation if they had been fully and accurately informed. They may

lose faith in the researcher and other authority figures, and even in the

merits of science in general.

When researchers deceive

subjects, their reputation for truthfulness may be harmed, as well as their

character. Scientists in general may

be less trusted if deceptive practices become widely known. And society may be

harmed, since deception could contribute to a general lack of trust and a

willingness by nonprofessionals to act deceptively themselves.

As researchers trick, deceive, and manipulate their subjects, they

thereby accustom themselves to denigrating other people's humanity. They may

also develop delusions of grandeur and omnipotence, and become progressively

more calloused and cynical, which could interfere with the integrity of their

scientific work.

Researchers need to rethink

the ethics, as well as the methodology, of some of the studies they propose,

since there will always be a delicate balance between the need to obtain

information that benefits humankind and the rights of individual subjects.[35]

In a Christian institution, research participants, as well as the constituency

and the general public, would doubtless expect a higher level of ethical

behavior than at a public institution.

Therefore, proposed research should be screened with care to ensure that

its methods and aims are consistent with the mission of the institution and the

moral principles of the denomination.

When planning an experiment,

the researcher should consider carefully the nature of the study to determine

whether deception is really necessary, and if so, then work out ways that

informed consent and subsequent debriefing can ameliorate the negative effects

of deception. Internal review boards

should look carefully at this issue and provide quite specific guidance to help

researchers resolve the problems through the application of ethical principles.

Privacy

Throughout the research

process, subjects' privacy should be carefully guarded. Social scientists

invade their subjects' privacy when they manipulate them into doing something

embarrassing or by disclosing private facts that place the subjects in a false

public light or intrude into their private domain. Having sensitive personal

information about a person means gaining power over that person, power that can

then be used to his or her detriment.

As a result, the person may be subjected to ridicule and intoleranceor

to legal or governmental action. His or

her community and descendants might even be harmed if the studies are used to

stereotype a particular ethnic group.

Personal interviews are

especially problematic, as the researcher's records on identified subjects may

be subpoenaed or used in legal proceedings against such persons, thereby

breaching the researcher's promise of confidentiality, putting the subjects at

risk, and possibly disrupting the researcher's work.[36] Therefore, invasion of privacy should be

undertaken only with greatest caution and after careful consideration of the

potential results.

The following questions are

central to assessing potential violations of privacy:

1. For what purpose(s) is the undocumented personal knowledge

sought?

2. Is this purpose a legitimate and important one?

3. Is the knowledge sought through invasion of privacy relevant

to its justifying purpose?

4. Is invasion of privacy the only or the least offensive means

of obtaining the information?

5. What restrictions or procedural restraints have been placed

on the privacy-invading techniques?

6. What protection is to be afforded the personal knowledge once

it has been acquired?[37]

With modern data processing

equipment, it has become much easier to run sophisticated analyses of

statistical information and identify the subjects of research, thereby

potentially endangering their welfare and privacy. Therefore, safeguards should

be taken to minimize any harm to subjects that might occureither by not

identifying them at all, or perhaps by using a number for each case, with the

code being destroyed after the analysis has been completed.

Recommendations

To help sensitize students

to the ethical and procedural dilemmas described above, Adventist colleges

should require ethics courses in each discipline. In addition, by reading about

current dilemmas in their fields of study, ethical issues involved in using

human subjects in research, and the codes of professional responsibility for

their professions,[38]

teachers can prepare themselves to discuss with their students the ways in

which Christian principles interact with real life.

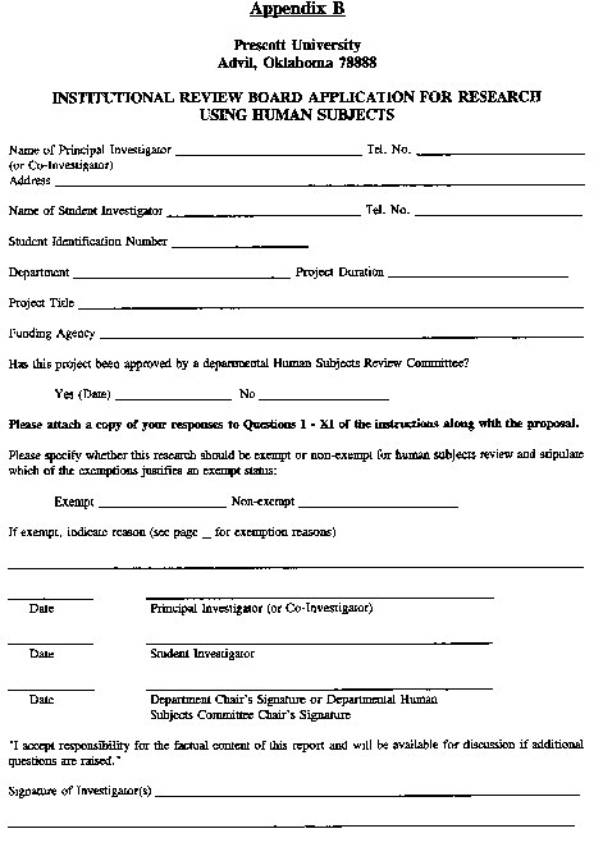

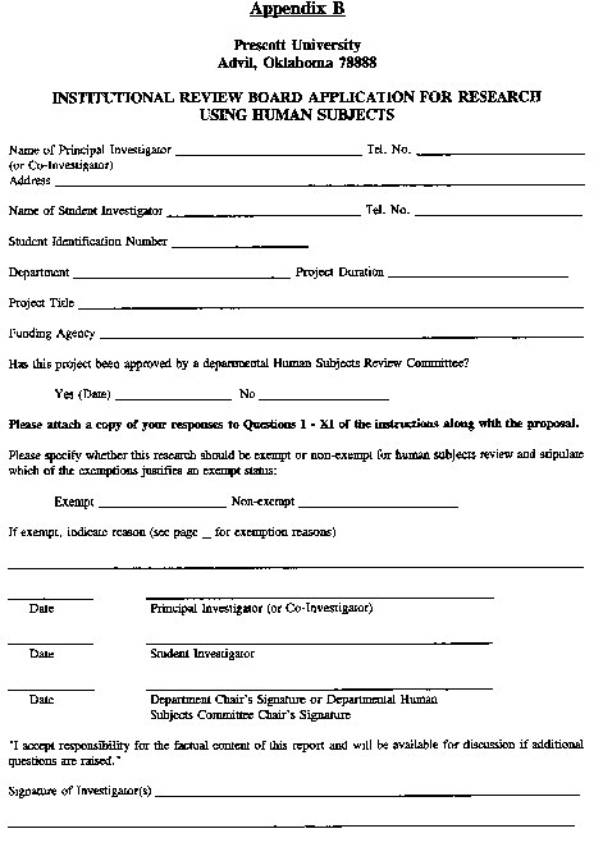

Colleges should set up

institutional review boards to screen proposed research by both professors and

students. (See Appendix A) These boards

should develop guidelines defining the boundaries of acceptable research and

describing the appropriate steps to implement such studies. These guidelines

should be disseminated to students, staff, constituents, and other interested

persons.

No one should be allowed to undertake any type of research that

involves human subjects unless he or she has obtained prior clearance from the

IRB and has signed a form indicating understanding of and assent to the

principles governing such research. Some of the areas that should be addressed

in the guidelines and consent form include the following?

Ψ

Ethical and

scientific design of the experiment/study, including potential usefulness of

the research versus drawbacks

Ψ

Methods of data

collection and storage, including provisions for ensuring confidentiality of

data

Ψ

Methods of

choosing subjects

Ψ

Types of

subjects to be used (special cautions should be included when children, the

elderly, minorities, marginalized groups, persons engaged in illegal

activities, or prisoners are included as subjects of research; or when the

researcher-subject relationship might affect the ability to freely give

consent)

Ψ

Promises and

commitments made to subjects

Ψ

Informed

consent, including debriefing of subjects and permission for them to withdraw

at any time without repercussions.

Ψ

Other ethical

considerations (lying to subjects, asking subjects to engage in unethical

behavior, conflicts of interest, etc.)

Ψ

Any laws or

government guidelines that apply to the research being done.

Ψ

Method of

presenting the findings

By following the above

suggestions, Adventist colleges and universities will be able to help their

students discover the exciting mysteries of science, while respecting and

benefiting God's crowning creation, humankind.

Selected Bibliography

Abelson,

Raziel, and Marie-Louise Friquegnon. Ethics for Modern Life. New York:

St. martin's Press, 1991.

Beauchamp, Tom

L., et al. Ethical Issues in Social Science Research. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins Unv. Press, 1982.

Braine, David,

and Harry Lesser, eds. Ethics, Technology, and Medicine. Aldershot:

Averbury, 1988.

Callahan, Joan

C., ed. Ethical Issues in Professional Life. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1988.

Christians,

Clifford G. and Catherine L. Covert, Teaching Ethics in Journalism

Education. Briarcliff Manor, N.V.:

The Hastings Center, 1980.

Curran,

Charles E. Issues in Sexual and Medical Ethics. Notre Dame: Univ. of

Notre Dame Press, 1978.

Durocher, Dbra

D. "Radiation Redux," American Journalism Review 16:2 (March

1994), p. 34.

Evans, J. D.

G., ed. Moral Philosophy and

Contemporary Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987.

Fletcher,

John. "Realities of Patient Consent to Medical Research," Hastings

Center Studies, 1:1 (1973), pp. 39-49.

Freud, Paul A.

Experimentation with Human Subjects. New York: George Braziller, 1970.

Fried,

Charles. Medical Experimentation: Personal Integrity and Social Policy.

Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co., 1974.

Gorlin, Rena

A., ed. Codes of Professional Responsibility. Washington, D.C.: The

Bureau of National affairs, Inc., 1990.

Gray, Bradford

H. Human Subjects in Medical

Experimentation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1975.

Holmes, Helen

Bequaert, and Laura M. Purdy, eds. Feminist Perspectives in Medical Ethics.

Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1992.

Jones, James

H., Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: The Free

Press, 1981.

Katz, Jay. Experimentation

with Human Beings. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1972.

Milgram,

Stanley. Obedience to Authority. New York: Harper & Row, Pub. ,

1974.

Myers,

Christopher, "Medical Researchers Pressed to Use Female and Minority

Subjects, "The Chronicle of Higher Education XXXVII:43 (July 10,

1991).

National

Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral

Research, "The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the

Protection of Human Subjects in Research (OPRR Reports, April 18, 1979).

OPRR Reports,

"Protection of Human Subjects, "Code of Federal Regulations 45 CFR 46

(Revised March 8, 1983).

Pellegrino,

Edmund D., et al., eds. Ethics, Trust, and the Professions. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Univ. Press,

1991.

President's

Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and biomedical and

Behavioral Research. "Implementing Human Research Regulations: The

Adequacy and Uniformity of Federal Rules and of Their Implementation."

Second Biennial Report, March 1983.

Public Health

Service, Department of Health and Human Services. "Answers to Frequently

Asked Questions." Rockville, Md., July 1984.

_______________. "FDA IRB Information Sheets"

(February 1989).

Rothman, David

J. Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics Transformed

Medical Decision Making. No City: Basic Books, 1991.

Sieber, Joan

E., ed. The Ethics of Social Research: Fieldwork, Regulation, and

Publication. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982.

Sire, James. Discipleship of the Mind. Downers Grove,

ILL: InterVarsity Press, 1990.

Sjoberg,

Gidean, ed. Ethics, Politics, and Social Research. Cambridge, Mass.:

Schenkman Pub. Co. Inc., 1967.

Swyhart,

Barbara Ann DeMartino. Bioethical

Decision-Making. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975.

White, Ellen

G. Education. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1903.

Zillma, Dolf,

and Jennings Bryant, "Pornography, Sexual Callousness, and the

Trivialization of Rape," Journal of Communication 32:4 (Autumn

1982), p. 11.

Appendix A

The

Responsibilities and Composition of and

Internal Review

Board

"An IRB is a board, committee, or other group

formally designated by an institution to review, to approve the initiation of,

and to conduct continuing review of biomedical [or social science] research

involving human subjects in accordance with FDA regulations [and the policies

and principles of the institution]. An

IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications in (to secure

approval), or disapprove the research. The purpose of IRB review is to assure

that:

v

"Risks to

subjects are minimized: (1) by using procedures which are consistent with sound

research designed and which do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk, and

(2) whenever appropriate, by using procedures already being performed on the

subjects for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

v

Risks are

reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the

importance of the knowledge that may be expected to result.

v

Selection of

subjects is equitable.

v

Informed

consent will e sought from each prospective subject or the subject's legally

authorized representative and will be documented in accordance with, and to the

extend required, by FDA's informed consent regulation.

v

Where

appropriate, the research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring the data

collected to ensure the safety of subjects.

v

There are

adequate provisions to ensure the privacy of subjects and to maintain the

confidentiality of data.

v

Appropriate

additional safeguards have been included in the study to protect the rights and

welfare of subjects who are members of a particularly vulnerable group.

Guidelines issued by the

U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services in 1988 suggest the following

criteria for membership in an IRB:

1. Each IRB should include

at least five members from varying backgrounds; each member should be qualified

through experience and expertise. Members should be chosen so as to achieve a

balance in the areas of race, gender, and cultural background. They should also be selected for their

sensitivity to such issues as community attitudes. This will help ensure respect for the IRB's work, particularly in

terms of safeguarding the rights and welfare of human subjects. IRB members should be able to assess the

acceptability of proposed research in terms of institutional commitments and

regulations, applicable law, and standards of professional conduct and

practice. If the IRB regularly reviews

research that includes vulnerable groups such as children, prisoners, pregnant

women, or mentally handicapped persons, it should consider including one or

more persons who are knowledgeable about and experienced in working with these

types of individuals. (One person might fill two or more of the above listed

notes)

Other sources suggest including a lawyer, a statistician, a layperson,

or a ethicist who specializes in the field of the proposed research. It would

be helpful for the institution's media specialist to attend meetings as an

observer, so that he or she can answer questions from the administration or the

press regarding the type of research being done at the institution.

2. Every effort should be made to ensure that both sexes and members

of different professions are included in the IRB.

3. Each IRB should include at least one member whose primary

concerns lie in scientific areas, and at least one member whose concerns are

primarily in nonscientific areas.

4. Members of the IRB should excuse themselves from voting on the

acceptability of any project that gives the appearance of a conflict of

interest with their work of their students.

Further guidance in forming

an IRB, identifying research studies that require oversight, determining

frequency of meetings, reporting requirements, and other protocol involved in

its operation may be found in the endnote sources, and by consulting the administration

of one of the administration of one of the numerous universities where IRBs are

currently operating.

Prescott University

Advil, Oklahoma 78888

Instructions for Completing the Application for Review of Research

Using Human Subjects

Please answer

the following questions, taking care to make the answers intelligible to

non-specialists.

I. Provide a

brief description of the research you are proposing.

II. Subject selection:

a. Who will be the subjects?

How will you enlist their participation? If you plan to advertise for subjects,

include a copy of the ad.

b. Will the subjects be

selected for any specific characteristics, e.g., age, sex, race, ethnic origin,

religion, or any social or economic qualifications?

c. If the answer to

"b" is Yes, state why the selection is made on this basis. (If

children are used, be sure to include forms used to solicit the assent of the

children as well as of their parents or guardians.)

III. What will be done to the subjects? Explain

in detail your methods and procedures in this area. If you are using a mailed

questionnaire or handout, please include a copy.

IV. Are there any risks to subjects? If so, what

are these risks? Can the observations, if known outside the study, place the

subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects'

financial standing or employability? What potential benefits will accrue to

justify taking these risks?

V. Explain what you plan to do with the

research findings.

VI. Explain how your procedures will protect the

privacy of subjects and maintain confidentiality of identifiable information at

all phases of the research, i.e., when collecting, coding, storing, analyzing,

and disposing of the data.

VII. Does the research deal with sensitive issues

such as illegal conduct, drug use, sexual behavior, or use of alcohol?

VII. State

specifically what information will be provided to the subjects about the

investigation. Is any of this information deceptive? State how the subjects'

informed consent will be obtained. Attach the form that will be used when

written consent is required.

IX. Describe the debriefing and follow-up

process you will use to explain the experiment and answer questions after the

research is completed.

X. Will electrical or mechanical equipment be

used? If yes, has it been checked for safety?

Please include 10 copies of

this form if the application if the entire IRB will be reviewing your application. Be sure to include all relevant supporting

documents include consent forms, letters sent to recruit participants,

questionnaires to be completed by participants, routing form for sponsored

projects, and any other materials germane to human subjects review.

XI. Other obligations: (a) Report to the

Institutional Review Board any unanticipated effects harmful to subjects that

become apparent during the research. (b) Cooperate with the continuing review

of this research project by submitting annual reports and a final report. (c)

Maintain all documents required by the institution and federal guidelines.

(This

sample form merges guidelines from SDA and public institutions. In the U.S., certain types of research are

exempt from more intense scrutiny. See federal statutes or local university

regulations for category definitions.)

Department of Health and Human Services, "Answers to Frequently Asked

Questions," FDA IRB Information Sheets (Rockville, Md.: Public Health

Service, FDA, February 1989), pp. 23,24; see also President's Commission for

the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and biomedical and Behavioral

Research, "Implementing Human Research Regulations, Second Biennial Report

on the Adequacy and Uniformity of Federal Review Rules and Policies, and Their

Implementation, for the Protection of Human Subjects" (March 1983).

"Institutional Review Boards, "Proposed Rules, Part 56, Section

56.107, Federal Register 53:218

(November 10, 1988).

"Answers to Frequently Asked Questions," p. 25.

[1]

"Bericht όber Eine bei Kindern beobachtete

Endemie infectiφser Kolpitis," Virchow's Archiv, Bd 99, Heft 2

(1885), ppl 263,264; cited in Jay Katz, Experimentation With Human Beings

(New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1972), p. 285.

[2]

M. H. Pappwoth, Human Guinea Pigs

(Boston: n.p., 1967), p. 61.

[3]

James H. Jones, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis

Experiment (New York: The Free Press, 1981).

[4]

Henry K. Beecher, "Ethics and Clinical

Research, "New England Journal of Medicine 74 (1966), cited in

David J. Rothman, Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics

Transformed Medical Decision making (No City: Basic Books, 1991), p. 16.

[5]

Reported by Sue V. Rosser, "Revisioning

Clinical Research: Gender and the Ethics of Experimental Design, " in

Helen Bequaert Holmes and Laura M. Rurdy, eds., Feminist Perspectives in

Medical Ethics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), p. 131.

[6]

After a two-year investigation, Massachusetts

Rep. Edward Markey in 1986 released a report detailing the experiments,

entitled "American Nuclear Guinea Pigs: Three Decades of Radioactive

Experiments on U.S. Citizens." Markey stated that officials had conducted

"repugnant" and "bizarre" experiments on hospital patients,

prison inmates, and hundreds of others who "might not have retained their

full faculties for informed consent" (reported by Debra D. Durocher in

"Radiation Redux, "American Journalism Review 16:2[March

1994], p. 35).

[7]

Dolf Zillman and Jennings Bryant,

"Pornography, Sexual Callousness, and the Trivialization of Rape,"

Journal of Communication 32:4 (Autumn 1982), p. 11.

[8]

Dorothy Nelkin, "Forbidden Research: Limits

to Inquiry in the Social Sciences, "in Tom L. Beauchamp, et al, Ethical

Issues in Social Science Research (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1982), p. 168.

[9]

L. Festinger, H. W. Riecken, and S. Schachter,

When Prophecy Fails (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1956),

reported by Joan Cassell, "Harms, Benefits, Wrongs, and Rights in

Fieldwork," in Joan E. Sieber, ed., The Ethics of Social Research (New

York: Springer-Verlag, 1982), p. 25.

[10]

Nelkin, in Beauchamp, p. 166.

[11]

Paul E. Freund, Experimentation With Human

Subjects (New York: George Braziller, 1970), p. xiii.

[12]

Nelkin, in Beauchamp, et al, p. 163.

[13]

Paul Ramsey, cited by Rothman, p. 96.

[14]

Beecher, cited by Rothman, pp. 82,83.

[16]

The whole text of the code reads as follows:

"Under no circumstances is a doctor permitted to do anything that would

weaken the physical or mental resistance of human being except form strictly

therapeutic or prophylactic indications imposed in the interest of his

patient" (cited by Charles Curran, Issues in Sexual and Medical Ethics [Notre

Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978], p. 77.

[17]

Eugene Fontinell, "Contraception and Ethics

of Relationships," in What Modern Catholics Believe About Birth

Control, cited in Barbara Ann DeMartino Swyhart, Bioethical

Decision-making (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), p. 49.

[18]

Robert C. Mortinmer, "The Standard of Moral

Right and Wrong," in Raziel Abelson and Marie-Louise Friquegnon, Ethics

for Modern Life (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1991), p. 20.

[19]

Henry Stob, Ethical Reflections: Essays on

Moral Themes (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1978), p.

130.

[20]

Ellen G. White, Education (Mountain View,

CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1903), p. 17.

[22].Hans

Jonas, "Philosophical Reflections on Experimenting with Human

Subjects," in Experimentation with Human Subjects, pp. 18-22; cited

by Curran, p. 87.

[24] The National Commission for the Protection of

Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, "The Belmont Report:

Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects in

Research" (OPRR Reports, April 18, 1979), p. 4.

[25] Mortimer in Ableson and Friquegnon, p. 15.

[26] Personal communication from John Wesley

Taylor, V, Ph.D., Director of University Research, Montemorelos University,

Mexico, February 24, 1994.

[27] David D. Rutstein, "The Ethical Design of

Human Experiments," in Freund, p. 363.

[28] Charles Fried, Medical Experimentation:

Personal Integrity and social Policy (Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co.,

1974), pp. 25,27

[30] Mortimer, in Abelson and Friquegnon, p. 19.

[31] John Fletcher, "Realities of Patient

Consent to Medical Research, "Hastings Center Studies, 1:1 (1973),

pp. 39-49.

[32] Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An

Experimental View (New York: Harper and Row, Pub., 1974).

[33] Alan C. Elms, "Keeping Deception Honest:

Justifying Conditions for Social Scientific Research Stratagems," in

Beauchamp, et al, pp. 235,236.

[34] Edward Diener and Rick Grandall, Ethics in

Social and Behavioral Research (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1978), cited in Beauchamp, et al, p. 169.

[35] If deception is considered absolutely essential

to the experiment, one researcher suggests using it only "when (1) there

is no other feasible way to obtain the desired information, (2) the likely

benefits substantially outweigh the likely harms, (3) subjects are given the

option to withdraw from participation at any time without penalty, (4) any

physical or psychological harm to subjects is temporary, (5) subjects are

d3ebriefed as to all substantial deception (Margaret Mead, "Research With

Human Beings: Model Derived From Anthropological Field Practice," in

Freund, p. 167).

[36] R. Jay Wallace, Jr., "Privacy and the Use

of Data in Epidemiology," in Beauchamp, p. 297.

[37]

W. A. Parent, "Privacy, Morality, and the Law," in Joan C. Callahan,

ed., Ethical Issues in Professional Life (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1988), p. 220.

[38].See for example, Clifford G. Christians and Catherine

L. Covert, Teaching Ethics in Journalism Education (Briarcliff Manor,

N.Y.: The Hastings Centerk 1980); and Rena A. Gorlin, ed. Codes of

Professional Responsibility (Washington, D.C.: The Bureau of National

Affairs, Inc., 1990).