3.1 In 1840 John Gait 11 of Williamsburg,

Virginia, USA, published a book on the therapeutic nature of library service,

which prompted a survey of American asylums. This led to his drawing up

guidelines governing patients' reading and book selection.

3.2 In the 20th century, trained librarians

began to administer hospital libraries.

3.3 The American

Library Association (ALA) sponsored programmes for the Armed Forces in WorldWar

I.

3.4 In 1916, Samuel Crothers used the word

"bibliotherapy" for the first time.

3.5 On

March 3, 1931, the American Congress passed legislation bringing library

services to the blind through Braille books.

3.6 After World War II, bibliotherapy moved

into educational and psychosocial areas.

3.7 In

1949, Carline Schrodes discussed in her doctoral dissertation the use of

bibliotherapy as a treatment method of psycho-therapy.

3.8 In 1962, Ruth Tews wrote an article for Library

Trends regarding bibliotherapy.

3.9 ALA

had the following professional representation at its annual conference in 1964

where an entire workshop was devoted to bibliotherapy, psychiatry, clinical

psychology, psychiatric nursing, social work, occupational therapy and of

course libraries.

3.10 In

June 1966 Congress passed the Library Service and Construction Act for the

improvement of both state institutional library services and services offered

to the physically handicapped.

3.11 An

information explosion has provided us with many forms of information media, i

e, printed and audio-visual materials which are used by counsellors and

therapists as tools for helping clients gain perspectives on their problems and

goals.

3.12 Bibliotherapy

has filtered into areas other than librarianship and the medical field, e g,

educational institutions.

The

brief review of the history of bibliotherapy demonstrates its continuing

vitality. It can be concluded that although the ancients were aware of the

therapeutic effects of reading, the practice of bibliotherapy is a relatively

now science. In order to understand better the evolution of bibliotherapy into

its present form, i e, that of directed reading and group discussion, one must

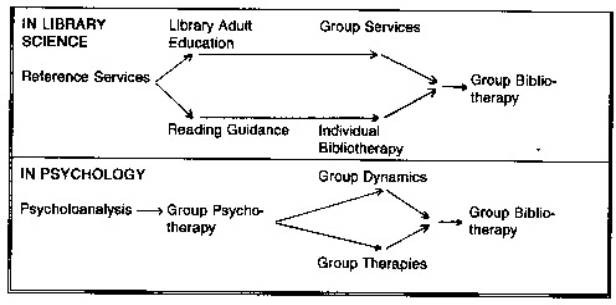

trace the roots of bibliotherapy in both library science and psychology.

4. ROOTS OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

4.1 In Psychology

Group

therapy was advocated in the 1920's by Burrow and Adler (Rubin: 1978), but it

was in the World War II era of 1939-1945 in which group therapy flourished. The

number of wounded soldiers needing therapy was overwhelming and there were too

many patients and not enough medical staff.

4.2

In Library Science

Margaret

Monroe (in Rubin: 1978) views bibliotherapy as part of the continuum of library

services. Reference services, reading guidance and bibliotherapy are closely

related functions, i e, all serve informational, instructional and guidance

needs. Unlike reference services and reading guidance, bibliotherapy is a

long-term approach to library services used for therapeutic purposes.

Librarians were also serving patients in hospitals and veterans on the streets.

The

following diagram summarizes the roots of group bibliotherapy (Rubin: 1978:

18):

ROOTS OF GROUP BIBLIOTHERAPY

5. BIBLIOTHERAPY AND THE INTEGRATION OF

FAITH AND LEARNING

The question may be posed as to what bibliotherapy has to do with the integration of faith and learning, and this will now be considered.

5.1 Once we accept that all truth is God's truth, we are committed

to do something, i e, not only words but also deeds. Integration of faith and

learning can take place on an individual level, i e, the teacher (Gaebelein:

1968). Ellen White also stresses the personal element in education:

"Christ in His teaching dealt with men individually.... The same personal

interest, the same attention to individual development, are needed in educational

work today" (1952: 231/2). In this process, the teacher is the

facilitator: "The educator's task is to inspire and equip individuals to

think and act for themselves in the dignity of persons created in God's

image" (Holmes: 1975: 16). One of the ways in which this may be done is

through discussion of books specifically chosen for certain individuals in

order to help them overcome emotional and behavior problems. Altmann and

Nielsen (in Marock,: 1983) claim that research substantiates this.

5.2 The purposes of educational bibliotherapy are diverse: to

impart information; to provide insight; to stimulate discussions about

problems; to communicate new attitudes and values; to teach new solutions to

problems; to enhance self-esteem; to furnish relaxation and diversion (Coleman

& Ganong: 1988).

5.3 In the educational situation,

bibliotherapy can be of two types, viz, corrective and preventive. In the

former, a teacher, counselor, or librarian attempts to solve an actual or

perceived problem of the student by presenting a book depicting a similar

situation. By reading the book the student gains insight, which may enable him

to solve his own problem. In the latter, a student is requested to read a book

containing a problem he may have to deal with in the future. In the reading of

the book, he may be better able to adjust, should a similar situation arise in

his own life (Stoneburg in Swart: 1984).

5.4 Literature abounds with information on reading as a therapy

(Stoneburg, Hutcheson, ALA in Swart). In summing it up, reading:

5.4.1 has a positive effect upon personality;

5.4.2 helps persons solve personal problems and

concerns;

5.4.3 Expands potential for growth and

development;

5.4.4 Provides instruction, knowledge,

understanding and inspiration.

6. COMPONENTS OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

The following

components will be discussed in turn:

*Aim

and related objectives

*Different

categories

*Types

of information media used

*Dynamics

of the aesthetic experience

6.1 The Aim and Related Objectives of

Bibliotherapy

Moses

(in Marock: 1983) lists the following aims of bibliotherapy:

6.1.1 To

give the person insights and solutions to his problems through identification

with the characters in the books he reads;

6.1.2 To inform and to explain to him the

complexities of human behavior;

6.1.3 To afford him the opportunity of liberation

from stress.

According

to Cilliers (1980), the main aim of bibliotherapy is to give insight and

discernment of problems so as to bring about a change in attitude and behavior.

Attitude is the way one thinks and feels and then reacts, while behavior is not

only conduct but what a person thinks he should do, i e, social norms, what

they normally do, i e, habits, and the results of the behavior.

THE AIM OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

|

Gaining

of comprehension and insight |

||

|

Change

in attitude and behavior |

||

|

Therapy |

Education |

Relaxation |

|

Emotional/Social |

Intellectual |

|

The

three long-term objectives shown diagrammatically, viz, therapy, education and

relaxation can be considered on three levels, i e, intellectual, social and

emotional. In other words, the therapy objective relates to the social and

emotional level, while the education objective to the intellectual level. The

objective in the area of relaxation is to make available to the client as a source

of compensation or reward information media to be utilized in his free time.

6.1.3.1 Therapy on the emotional level helps the client

to understand his psychological and physical reactions to frustration and

conflict and to gain a clearer understanding of his motives and needs. Help is

obtained through different types of information media, e g, books and films,

where he can read and see how others have handled problems similar to the ones

he is facing. As Schlabassie (in Cilliers: 1980: 30) stated succinctly, it is

"providing vicarious experience without immediately exposing oneself to

the dangers of actual experience." The client is then encouraged to

discuss his problem freely.

6.1.3.2 Therapy on the

social level involves the evaluation of values through information media.

Through constant contact with characters in the information media, he develops

a social sensitivity and through observing their needs and aspirations, he

makes application in his own life. The family and the church can provide assistance

by helping him to absorb cultural patterns.

6.1.3.3 Education on the intellectual level concerns

the stimulation of new creative interests, development of the idea that there

is more than one solution to a problem, and encouragement of positive and constructive

thinking. Through the information media, the client is faced with the problem

he is experiencing and it is discussed objectively with a view to finding a

possible solution (Cilliers: 1980).

6.2

Categories of Bibliotherapy

Three

categories of bibliotherapy may be distinguished, viz, institutional, clinical

and developmental (Cilliers: 1980).

6.2.1 Institutional

bibliotherapy uses didactic information media for individual institutionalized clients. It embraces

the medical and psychiatric use of bibliotherapy, with a person-to-person

situation through a bibliotherapist working with a medical team.

6.2.2 Clinical

bibliotherapy uses imaginative information media for groups of clients with

emotional and behavioural problems. The team is made up of a bibliotherapist

and a clinical worker seeking the attainment of insight and change in conduct

and behavior.

6.2.3 Developmental

bibliotherapy uses imaginative or didactic information media or a combination

of both with groups of normal individuals in the community. The bibliotherapy

group is led by a bibliotherapist and an educator to foster normal development,

self-realization and mental health.

A

noticeable characteristic common to all categories is that a discussion must

take place about what is read, seen or heard.

6.2.4

Summary of the Categories of

Bibliotherapy (Rubin: 1978: 7)

|

|

Institutional |

Clinical |

Development |

|

Format |

Individual or group; Usually passive |

Group-active; Voluntary or involuntary |

Group-active; Voluntary |

|

Client |

Medical or psychiatric Patient, prisoner, or client in Private

practice |

Person with an emotional or behavioral problem |

"normal" person, often in a crisis

situation |

|

Contractor |

Society |

Society or the individual |

Individual |

|

Therapist |

Physician & librarian team |

Physician, mental health worker, or librarian,

often in consultation |

Librarian, teacher, or other |

|

Material used |

Traditionally didactic |

Imaginative literature |

Imaginative literature and/or didactic |

|

Technique |

Discussion of material |

Discussion of material, with emphasis on

client's reactions and insights |

Discussion of material, with emphasis on

client's reactions and insights |

|

Setting |

Institution or private practice |

Institution, private practice or community |

Community |

|

Goal |

Usually informational, with some insight |

Insight and/or behavior change |

Normal development and self-actualization |

6.3 Information Media Appropriate for use

in Bibliotherapy

6.3.1 Principles of selection of materials (Rubin:

1978):

6.3.1.1 Materials with which the therapist is familiar

must be used, i e, literature

suggested

must have been read, videocassettes previewed.

6.3.1.2 When selecting

materials, the therapist should be conscious of length short works are

physically easier to read and recall.

6.3.1.3 Materials should be applicable to the problem

but not necessarily identical to it.

6.3.1.4 Choice of materials should be influenced by the

reading ability of the client.

6.3.1.5 Chronological

and emotional age is an important factor and should be reflected in the

sophistication of the selected material.

6.3.1.6 Reading

preferences are also a guideline for selection, e g, children and adolescents

go through different stages and reading preferences change. For example, during

the early stages, interest is in animal and adventure stories, etc, and later

the interest changes to stories of romance, war, and adolescent life.

6.3.1.7 The therapist

should learn to know the client well so that materials expressing the feeling

or mood of the client can be selected.

6.3.1.8 Cartoons and comics, which have been carefully

considered, may also be used.

6.3.2 Media suitable

for use in bibliotherapy include written and audio-visual materials, both

subject and imaginative.

6.3.2.1 Subject literature can be divided into

empirical, natural and social sciences, technology and humanities. The goal of

this type of literature is to help the client to a better understanding of his

environment and of reality.

6.3.2.2 Imaginative

literature (belles-lettres) is made up of novels, drama, poetry, short stories

and essays. This type of literature is concerned with the affective reactions,

and imagination incorporating the will and intellect. This type of literature

has a greater potential than subject literature to change an individual. It

broadens the understanding of personal motivation and cultural conflicts.

Schrodes (in Cilliers: 1980: 37/38) states that "psychiatrists and

psychologists generally acknowledge that great artists are penetrating

interpreters of the personality ... have intuitively plumbed the depths of the

human psyche and emerged with incisive descriptions of the dynamics of the

personality."

6.3.2.3 Audio-visual media are also used in

bibliotherapy and here we also have subject and imaginative information. Forms

are films, record players, tape recorders, videocassettes, radio and television

programmes. At times this is the only form of information media that can be

used for certain

client groups, e g, illiterates, those with low educational levels, and the

bored. Audio-visual media are non-demanding and non-anxiety provoking. They can

be used for large groups of clients and the reaction is instantaneous and

intense but not long lasting. Films are more direct and immediate than books

and elicit a high degree of recall. Music can also be used and as Juliett Alvin

(in Cilliers: 1980: 30) says, "it works through the effects of sound on

man who is a resonant body able to perceive and to emit sound. ... The

influence of music on man's behavior has been used universally as a healing

power by magic, religion and medicine."

According

to Klapper (in Cilliers: 1980: 38), the radio will reach people, which

literature and films will fail to do. This audience tends to be more

suggestible than the audience of other media. Clients can listen as a group.

Television is another medium which Michael Novak (in Cilliers: 1980: 30/40)

describes as "a moulder of the soul's geography. It builds up

incrementally a psychic structure of expectation." Programmes can be

discussed and this stimulates informative needs. However, only a limited number

of personal emotions, situations and motives can be handled. No research has

yet been carried out in comparing the therapeutic effects of literature and

audio-visual media.

Loevinger

(in Cilliers: 1980: 40) postulates a reflective-projective theory of mass

communication, which is closely related to the theory of bibliotherapy, viz,

"while the mass media reflect various images of society, the audience is

composed of individuals, each of whom views the media as an individual. The

members of the audience project or see in the media their own visions or images

in the same manner that an individual projects his own ideas into the inkblots

of the Rorschach Test commonly used by psychologists."

6.3.3.4 Particularly in the context of the integration

of faith and learning, God's "two books", Scripture and nature,

provide a wide spectrum of subject and imaginative exposure, both verbal and

non-verbal, and these yield many opportunities for bibliotherapy in all its

aspects. "Nothing is so calculated to enlarge the mind and strengthen the

intellect as the study of the Bible. No other study will so elevate the soul

and give vigor to the faculties as the study of the living oracles"

(White: 1977: 93). "There is no position in life, no phase of human

experience, for which the teaching of the Bible is not an essential

preparation" (White: 1958: 599). Bible stories and especially the poetry

in the book of Psalms can be used.

6.4 Dynamics of the Aesthetic Experience

As

has been stated, didactic information media are instructive and informative,

while imaginative information media stimulate the imagination. The latter [ends

itself more to the accomplishment of an emotional experience where the

emotional processes develop parallel with the primary phases of traditional

psychoanalysis (Cilliers: 1980): identification, projection, introjection,

catharsis, insight.

6.4.1 In identification the client identifies himself with the chief

character under study. As a result, the formation of values and social attitudes

occur.

6.4.2 Through

projection, the problem is projected outside the personality; blame can be

placed on someone else.

6.4.3 The opposite

of projection is introjection and here mistakes are accepted and placed on

oneself instead of on others, i e, we internalize and put into ourselves the

superego whose still, small voice reminds us of the values of our parents and

society. A common example here is the identification with heroes and heroines

who are admired.

6.4.4 The concept

"catharsis" originated with Aristotle who looked upon it as a

cleansing and purging through the expression of feelings. One reacts to the

symbolic experience in literature as if it is an actual experience.

6.4.5 Finally, insight and integration start the

change of personality (Cilliers: 1980, and Lewin:

1981).

6.4.6 Norman Holland (in Cilliers: 1980), a

literary critic and psychoanalyst, lists the following principles of the

literary experience:

6.4.6.1 Style seeks itself, i e, readers react

positively to material that fits in with their wishes and needs;

6.4.6.2 Defenses must

be matched, i e, readers are attracted to characters who have similar defense

mechanisms as they do as well as emotional values;

6.4.6.3 Fantasy projects fantasy, i e, personal fantasy

is projected onto the story;

6.4.6.4 Character

transforms characteristically, i e, a work is understood when the reader

translates it into his inner language, taking into consideration his education,

character, needs, defense mechanisms and fantasy.

These

principles of Holland reflect the idea that reading is an active process where

the reader creates for himself a now experience-world that fits in with his

needs, motives, experience and personality.

The

processes identification, projection, catharsis and insight are closely related

to the needs and motives of the reader. All personal needs are covered by the

following:

Material,

spiritual and social security needs, self-actualization, relaxation and

aesthetic needs.

6.4.7 Three forms of needs are identified:

6.4.7.1 Inactive needs - the most difficult to evaluate

as they must first develop before they can be activated;

6.4.7.2 Unspoken needs

- there is an awareness of these but they are not satisfied; they need to be

stimulated and given direction

6.4.7.3 Outspoken needs - spoken about and can usually

be satisfied (Cilliers: 1980).

These

needs must be identified in order for the practice of bibliotherapy to be

successful.

6.4.8 For the purpose of this study, the following

motives are important:

6.4.8.1 Cognitive motives, i e, adjustment, orientation

and interpretation motives;

6.4.8.2 Prestige motives, i e, need for self-respect;

6.4.8.3 Escapist motive, i e, reading for relaxation to

escape conflict and frustration;

6.4.8.4 Aesthetic motive, i e, literature that appeals

to the imagination;

6.4.8.5 Religious motive.

These

reading motives can reconcile the person's basic cognitive and aesthetic needs

and also the needs for recognition, self-actualization and relaxation.

7. THE PROCESS OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

The

bibliotherapeutic process is activated by a client with a problem brought to

the attention of the bibliotherapist. The bibliotherapist with the co-operation

of the client and a multidisciplinary team sets the process going. The clinical

worker diagnoses the problem and prescribes the handling, while the

bibliotherapist selects the subjects of imaginative media and makes these

available to the client. The client is the active one in the process and reads

looks or listens. After this the client discusses what he has read, seen or

heard with the bibliotherapist and the group. The problem is analyzed and

insight and understanding brought about. The ideal is then for the client to

accept this insight and understanding which will change his attitude and

behavior.

7.1 Personal Characteristics

The

bibliotherapist should have the following personal characteristics: empathy,

warmth and honesty, sensitivity, emotional stability, fairness, humor,

initiative, receptiveness for change, ability to communicate verbally and non-verbally,

objectivity, healthy judgment, intuition, self-assurance, authority to get

things done. He needs to understand people thoroughly, have a wide knowledge of

books, and be sympathetic to human needs. This indicates a congruent, genuine

and integrated person. He also needs the ability to suggest the right reading

material tactfully and without being too obvious. Practicing bibliotherapy

cannot be made to appear too simple, or it is possible to do more harm than

good

7.2 Education of the Bibliotherapis

Besides

the above-mentioned characteristics, those practicing bibliotherapy felt that

the following would be beneficial courses in addition to the subjects necessary

for their undergraduate degrees or diplomas in selected disciplines, viz,

librarianship-user studies and readership, psychology, literature and

counseling (Rubin: 1978).

7.3 Methods Used

For

bibliotherapy to be effective it must begin early, at the first sign of an

emerging problem. The following methods may be used in bibliotherapy:

7.3.1 Individual bibliotherapist and individual

client meet to discuss information media;

7.3.2 Subject literature is read out aloud and

then discussed: This is the oldest method;

7.3.3 The client reads literature in his free

time, i e, prepares for the session;

7.3.4 Photocopied

imaginative literature is read out aloud combined with music. This method

involves all and the reactions are spontaneous.

7.3.5 A combination of therapeutic reading and

writing;

7.3.6 Look-and-listen to audio-visual media followed

by discussion.

No

matter what method is used, a discussion must always take place. This

cannot be overemphasized as a amount of reading or watching of audiovisual

materials can substitute for the vital give-and-take exchange between therapist

and client. "Unless such a relationship is somewhere in the background,

whole libraries ... will be of no avail" (Alston in Rubin: 1978: 32).

8. MILIEUS OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

Bibliotherapy

can be considered in our environs, viz, medical, psychiatric, educational, and

rehabilitative.

As

indicated previously (see section 3), bibliotherapy, especially in the USA, is

moving into other fields, e g, education and librarianship. As the barriers

between institutions and society are broken down, the special services of

hospitals and institution libraries, including bibliotherapy, take on a

universal meaning in librarianship. The work is pioneered in the institution

and then has a broader application in public and school libraries (Cilliers:

1980).

8.1 Bibliotherapy

is applied mostly in the general medical milieu, i e, hospitals. Patients have

medical, psychological and social problems and here bibliotherapy can be

practised. A wide variety of problems are treated in the hospital and this is

an excellent environment in which to use bibliotherapy, as a therapeutic team

is always available. The category of bibliotherapy used here is institutional

and clinical.

8.2 Another

milieu is the psychiatric and the type of client treated here is the neurotic,

manic-depressive, paranoid psychosis, schizophrenic, those with brain damage,

alcoholics, drug addicts, those with old age problems and those with venereal

diseases. Categories used here are institutional and clinical. Despite the fact

that many may not be able to express themselves clearly, bibliotherapy can

still be used with books, newspaper articles, radio and television programmes,

films, slides, music, followed by a discussion. "Bibliotherapy in the

psychiatric field is utilized in conjunction with other treatment techniques

such as psychodrama, hypnosis, and insulin shock treatment, among others. It is

also utilized with various psychopathogenic syndromes such as neurosis,

functional psychosis and a variety of personal problems" (in Cilliers:

1980: 56).

8.3 In the

educational milieu, books can play an important part. An attractive school

library or media center is a vital aid to bibliotherapy in this area.

Educationists and bibliotherapists can work together. Clients are pupils,

students, adolescents, and persons with problems in the community. Corrective

and preventative bibliotherapy is useful here. Categories of use here are

institutional, clinical and developmental. Books must be well chosen and

carefully analyzed. Teacher and bibliotherapist can decide on what method to

use. "Inasmuch as the building of a wholesome, self-confident,

self-respecting, effective, happy personality is one of the major goals of

education, the teacher is seeking constantly to find ways of giving each child

the particular guidance that he needs. One of the ways in which such guidance

can be given is through suggestions for reading in which the child may receive

mental and emotional therapy through identification with a character in a book

who faced a problem or situation similar to the child's own problem or

situation" (Cilliers: 1980: 57).

8.4 The

rehabilitation milieu includes prisoners, alcoholics, drug addicts, and the

mentally retarded. Bibliotherapy is seldom used here as it is still as yet

underdeveloped in this milieu. In institutions, these persons are kept busy but

work is usually stereotyped. They do enjoy social activities and doing

something new and stimulating. Cagetories which can be used here are

institutional and clinical.

A

client is any individual who needs help from a professional person. In

bibliotherapy the professional person is the bibliotherapist and the clients

are children, adolescents, adults and the aged who need help. As indicated

above, the bibliotherapist needs to understand the type of client he is working

with, i e, all facets of his life in order to build up a bond of trust.

9. LIMITATIONS OF BIBLIOTHERAPY

The

benefits of bibliotherapy have been well documented, but there is a potential

for harm that exists during bibliotherapy, particularly when implemented by a

novice. The selection of a wrong book, cassette, video, etc, at the wrong time

for a client can aggravate a situation.

Cornett

and Cornett (1980) list the following limitations:

9.1 Readiness of the client

to be seen in a mirror.

9.2 Skill of the therapist in directing the

process through all the necessary steps, especially the follow-up.

9.3 Degree

and nature of the client's problem.

9.4 Availability of quality

materials.

9.5 Manner in which the

material is presented.

9.6 Tendency of some to

rationalize away problems when reading about them.

9.7 Limitations of the

process - problems are not always fully resolved when reading about them.

9.8 Ability of the client to

transfer his insight into real life.

9.9 Using literature as an

escape mechanism and retiring into a world of fantasy.

9.10 Interrelationship between

bibliotherapist and client.

9.11 Availability of training

programmes and courses in bibliotherapy.

"Bibliotherapy

is not foolproof, nor is it a panacea. It is a worthy adjunct to other methods

of helping people cope with needs that arise in life" (p 39).

10. CASE STUDY

Two

mothers approached the author of this paper (referred to as the investigator)

to help them to solve certain problems, by using bibliotherapy, that they were

experiencing with their teenage daughters at home. The two teenagers had worked

for the investigator in the College library after school for a number of years.

They were excellent workers, and both enjoyed reading. The investigator, having

worked with young people in the educational field for over thirty years as

teacher, principal, minister, dean and professional librarian, fell qualified

to conduct the bibliotherapy sessions with the teenagers, and the investigation

was undertaken with the permission and full co-operation of the parents of the

two girls.

The

book, By the shores of Silver Lake, by Laura Ingalls Wilder, was

selected from a list received from ISKEMUS (see note on page 17) after the

director had been briefed about the project. While it is true that this book is

primarily for younger children, the director pointed out that it is still

enjoyed by all age groups. In this book, the author tells of the problems her

family faced when moving out West in the latter part of the last century, her

sister blinded by scarlet fever and her father having to earn a living at a

railway camp. In describing this period of her life, she reflects the

interaction among the different members of the family and one gets a clear

picture of each member - each one's likes and dislikes, moods and feelings, and

the atmosphere in the home. The latter point is important because the two

teenagers had a family relationship problem and this book was chosen in an

endeavor to rectify it. As Frank stated (in Crompton, 1983, p 122),

"reading ... gives children a greater insight into themselves and helps

them grow in appreciation of other people, in understanding the world they live

in and the forces which operate to make people think, feel and behave as they

do."

The

two girls in question were asked to read the book in their free time, and an

appointment was made for the first bibliotherapy session. They had not been

made aware of why they had been selected, but had been asked to help the

investigator with a project, to which they agreed with alacrity. Sessions were

conducted with the teenagers separately. In the first session, the book was

discussed, with the teenagers doing most of the talking. Characters were

analyzed, the way of life observed, and then lessons drawn. During the second

session, they were asked to read an assigned page of Little town on the

prairie by the same author and then write down their reactions. The parents

of pupil A became involved to the point where the investigator worked with them

as he felt that they were adding to the problems of the pupil. They accepted

this and several meetings were held to monitor the progress of their daughter.

They were given two books to read, viz, How to really love your teenager by

Ross Campbell, and The strong-willed child by James Dobson.

10.1 Sessions with pupils

10.1.1 In the first session, pupil A was not afraid

to talk and needed prompting only occasionally. She made the following

observations about the relationships among Pa, Mother, Mary and Laura:

She

could be Laura (pupil 13 years of age too)

Identified

with Pa more than with Mother

Pa did not complain

but did things with Laura

Realized

that Mother was strict because she wanted Laura to be a lady

Pa

had the same in mind, but went about it more diplomatically

At times Laura seemed

older than her 13 years

The whole family

seemed happy

Mary

always said exactly what she meant Laura appeared to enjoy life.

A

discussion on the above followed. When asked to predict the future for Laura,

Pa and Mother, pupil A responded that Laura and Pa would stay the same, whereas

Mother would mellow, or possibly become stricter. After reading the extract

from the second book, pupil A made the following written comments:

Laura

was content to remain on the farm, liked the out-of-doors, loved to be free and

not cooped up in a town; Pa was open-minded but still held to his principles;

Ma was prim and proper, dubious about all strangers, very protective of the

world, and wanted what she felt was best for them.

10.2 Pupil B (13 years of age) reacted as

follows to the first session:

She enjoyed old-type

stories

She could be Laura

(same age)

Laura

was an interesting person, willing to help, considerate of others (e.g, always

willing to help Mary)

The

family relationship was good, i e, they sang together, were on time for meals, all

helped each other, showed respect for each other

Identified

with Pa; Mother reprimanded too much; Pa did things with Laura

Mother

was strict; she wanted her daughters to be ladies

Mother

was too busy to listen, whereas Pa always listened

Pa

seemed to be easy going but had high standards

They

were satisfied with what they had and did not complain

Respected

Pa and Mother

When

asked to predict the future for the family, she replied that Laura would stay pleasant

and happy, Pa would remain the same, and Mother would mellow after Laura was

married and that her children would influence Mother. A discussion followed.

In

the second session, pupil B wrote as follows after reading the extract:

Pa

was always willing to let his girls have a chance at seeing and experiencing a

different way of life. He would only let his girls have those chances if he

thought it was good for them; if he thought it was bad, he would explain why.

Mother

was reluctant to let her girls do something different. She wanted to keep them

from evil and thus protected them. Mother was quick to answer, then apologized

when she realized she had not even considered it.

Laura

was curious yet timid and in same ways did not want things to change as long as

all were happy.

10.3 Analysis

An analysis of the

responses by both the teenagers indicated the root of their problems. Pupil A

came from a home where the mother played the dominant role. She had to do this

because the father was quiet and retiring. The mother was strict and because of

the phase that pupil A was going through, communication had broken down between

her and her parents. She realized that her mother wanted what was best for her,

but felt that her mother's approach was wrong. Pupil A was outgoing and did not

like "to be cooped up". She admitted that she was influenced by what

she read. The investigator felt that she understood her mother and saw her in a

different light after the discussions. She accepted that her parents wanted

what was best for her and that she could not just "go wild" and

"do her own thing" without considering the consequences. Work in the

library and sport subsequently gave her more freedom.

The

parents were also advised of the results of the sessions and promised to read

the two books mentioned above. It was suggested that the mother let the father

become more involved in helping his daughter overcome her problems, e g,

relating to her parents. A bond of trust had to be built up between parents and

daughter.

Pupil

B also came from a home where the mother played a dominant role because the

father was a workaholic and was never at home. Pupil B was becoming bossy and

did not relate well to the other members of the family, i e, one sister and

three brothers. Her response indicated that she would like the family to do

things together because they all go their own ways and even eat at different

times - hence her observation in the first session regarding togetherness. She

also realized that her mother was pushed into the role of running the home. She

longed for a home like Laura lived in.

In

this instance, she realized after discussion that she could respond to all the

members of her family and be helpful. She also expressed a willingness to see

things from her mother's point of view - who wanted what was best for her. She

felt that the father should pull his weight in the family.

It

was fascinating to see how the two pupils projected themselves into the story

and developed a world they would like to live in. Different methods used

produced similar reactions from the pupils.

10.4 Correlation with Literature Survey

10.4.1 Books

specifically chosen for certain pupils can help them to overcome emotional and

behavioral problems (5.3,5.4)

10.4.2 Aims of bibliotherapy were partially realized

(6.1)

10.4.3 Developmental category used (6.2.3,6.2.4)

10.4.4 Imaginative media used (6.3.2.2)

10.4.5 Phases of traditional psychoanalysis

experienced (6.4)

10.4.6 Recommended methods used - 3rd and 5th methods

(7.3.3,7.3.5)

10.4.7 Educational milieu (8.3)

10.5 Conclusion

Despite

the short time factor, it was very satisfying to note that the investigator

found the basic cause of the problems and was able to point the way to possible

solutions.

11. EVALUATION

Three

methods may be used to evaluate the bibliotherapy programme:

11.1 Subjective evaluation

relies upon the feedback from the client.

11.2 The

experimental method of evaluation consists of setting up two groups - one

taking part in bibliotherapy and a non-participating control group.

11.3 Self-evaluation on a

grading scale.

12. REPORTING

With

regard to reporting in bibliotherapy, three types of records may be kept:

12.1 Internal

records for future use by the bibliotherapist with relevant section headings,

subject areas and commentaries on reactions.

12.2 External

records can help in the treatment of clients when one wants to check back to

see what problems existed and method of treatment.

12.3 Records for

research into living habits and behavior, etc, and include personal details

such as age, education, socio-economic position and analysis of problems.

13. CONCLUSION

13.1 Bibliotherapy

is compatible with the goals of Seventh-day Adventist education of the

harmonious development of all the faculties. The tradition of small classes and

personal attention to each individual by the teacher sets the stage for the

close liaison necessary between the bibliotherapist and his client.

13.2 Bibliotherapy

can be used in our educational institutions in both the preventive and

corrective fields to help students to explore and challenge values, to

"prove all things (and) hold fast to that which is good" (I Thess

5:21), to develop that power of discernment that forms the basis of a solid

Christian character.

13.3 Bibliotherapy

can be used correctively to be of assistance to students from divided homes,

those on drugs and alcohol, stepfamily members, those with emotional problems

like loneliness, hatred, selfishness. It can also be used preventatively in

helping students master life skills.

13.4 Porterfield

(1967:1) speaks about "the literary mirror" and states: "there

you are, looking at yourself in the very pages before you - a clear picture

drawn by an author who never saw you." Through the ministration of a

trained bibliotherapist, you can also see yourself as you ought to be and can

be - and will be.

NOTE:

1. Many books written by Seventh-day

Adventist authors could be used in bibliotherapy.

2. ISKEMUS, the Information Center for Children's Literature

and Media of the University of Stellenbosch has drawn up select bibliographies

for all age groups listing books, which can be used in bibliotherapy.

Bibliographies on Adoption, Single Parent Families, Survival, Living with Youth

Adults, The Gifted, War, Young Love, etc. The author is prepared to obtain from

ISKEMUS any bibliographies requested.

BIBLIOGRAPH

Carpenter,

H and Prichard M 1984. The Oxford companion to children's literature. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Cilliers,

J 1 1980. Bibliotherapy for alcoholics and drug addicts (Unpublished

doctoral dissertation). Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch.

Coleman,

M and Ganong, L H 1988. Bibliotherapy with stepchildren. Springfield,

Illinois: Charles Thomas.

Cornett,

F C and Cornett, C E 1980. Bibliotherapy: The right book at the right time. Bloomington,

Indiana: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Crompton,

M 1983. Respecting children: social work with young people. London:

Edward Arnold.

Gaebelein,

F E 1968. The pattern of God's truth. Winona Lake, Indiana: BMH Books.

Haldeman,

E G and Idstein, S 1979. Bibliotherapy . Washington, DC: University

Press of America.

Holmes,

A F 1991. The idea of a Christian college. Grand Rapids, Michigan:

Eerdmans.

Levin,

Lydia 1981. Bibliotherapy: A general discussion relating to the reader, the

librarian, and its therapeutic potential. In: Libri Natales 12(7),

January: 7-17.

Marock,

D L 1983. Reading reluctance among children. (Unpublished MA thesis).

Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Porterfield,

A L 1967. Mirror for adjustment. Fort Worth, Texas: Texas Christian

University.

Rubin,

R J 1978. Using bibliotherapy. Mansell, London: Oryx Press.

Swart,

M H G (compiler) 1984. School media center: Media use in schools.

Pretoria: Transvaal School Media Association.

White,

E G 1946. Counsels to writers and editors. Nashville, Tennessee:

Southern Publishing.

______

1952. Education. Mountain View, California: Pacific Press.

______

1977. Mind. Character and personality, Vol 1. Nashville, Tennessee:

Southern Publishing.

______

1958 Patriarchs and prophets. Mountain View, California: Pacific Press.