Institute for Christian Teaching

Education Department of Seventh-day Adventists

A RATIONALE AND MODEL OF A

WORK EXPERIENCE PROGRAM

FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS IN

PHILIPPINES

By

Jonathan C. Catolico

Director

Departments of Education and Communication

South Philippine Union Mission

Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

Prepared for the

Integration of Faith and Learning Seminar

Held at

Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies

Lalaan 1, Silang, Cavite

July 18-28, 1993

142-93 Institute for Christian Teaching

12501 Old Columbia Pike

Silver Spring, MD 20904, USA

INTRODUCTION

The prime function of education is to prepare men and women for life and service. As such, it does not only develop the mental, moral, and spiritual faculties but also the physical powers of man.[1] This is not an easy task for educators to perform. It demands special facilities and equipment, qualified teachers with special talents to match the need, and above all, dedication and commitment on the part of the teachers and school administrators to achieve the purpose as envisioned in the mission of every Seventh-day Adventist College. However, though hard it may seem, this calls for immediate action to a more practical training for our youth.

Ackerman relates that a trend toward this purpose was observed during the last of the nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century. It was at this time when John Dewey experimented on this activity at the University of Chicago.[2] Since then, many great educational leaders have seen the importance of a work-study experience program for the youth.

The concern that the educators and government leaders had on this matter was manifested in their efforts to assist the youth where the latter could best serve society. This program fits well into the program of the Seventh-day Adventist educational system as outlined by E. G. White:

Schools should be established that, in addition to the highest mental and moral culture; shall provide the best possible facilities for physical development and industrial training.[3]

Education, therefore, has become an important commitment and responsibility of the Seventh-day Adventist Church from its earliest period of organization and development.[4]

This writer was intrigued and saddened by a chorus of almost similar answers to the query on how effectively the work experience program (WEP) achieves the goals as set forth in the writings of Mrs. White. A deadening answer points to the WEP as almost a "thing of the past." With this as a backdrop, the writer will attempt to provide a rationale for the need of maintaining a program of work and a model for college students in the Philippines and a conceptual framework to determine the factors correlated with an effective work experience program. Due to limited space, the reader is directed to the endnotes for a better grasp of the topic.

In this paper, work experience program is defined as a component in the college curriculum, whereby a student goes through a work activity, which introduces him to the world of work. This also includes manual training but not necessary limited to it. In simpler term, it is defined as experimental learning.

In the Philippines, Mountain View College (MVC) and Philippine Union College (PUC) had been the institutions described as models for work program by the Philippine government during the '80s and early '70s. This was reported by Dr. Raymond Moore in his book, Adventist Education at the Crossroads.[5] Dr. Agrifino Segovia also mentioned about this in his 1965 study.[6] MVC and PUC's adherence to the philosophy of work created some desires among administrators of non-SDA institutions and government educational leaders to implement similar programs on their campuses. At present, however, the picture has changed. A survey of the major reasons for the decline of emphasis on work program reveals the following:

1. Size of enrolment. In the early years of MVC and PUC, enrolment was low but as the enrolment grew, there was not much work departments to accommodate thestudents. Evidently, there were few work opportunities for all students.

2. Academic pressures on college teachers. With the increase in enrolment, heavier academic load were assigned to teachers thus reducing their time to supervise work programs.

3. Change in the academic environment in society. A shift was seen from technical/vocational to science/medical courses and other courses, which were highly academic in nature.

4. Change in attitude of students. Students equate manual labor with low status in society. The dignity of labor is misunderstood. The more affluent students refuse to work.

5. School industries are financially losing with student labor. Inexperienced students doing jobs, which require skill was believed to be contributory to the losses, incurred by the school industries. Also, work requiring much longer time does not benefit much from students who only put two or three hours of work per week.

RATIONALE

As leaders of the educational system in the Seventh-day Adventist Church we cannot just fold our arms and close our eyes and say, "Well, this is the reality," and from this juncture we approach the issue by "satisficing" or by shrugging our shoulders. We cannot now renege from our duties of providing a kind of education that will place our youth in "an acceptable condition with God."[7] Tumangday gives an important rejoinder by saying:

Our best thinking and most earnest efforts are called on as we educators accept the ongoing challenge of producing educational programs that will facilitate, foster and revitalize the work of restoration.[8] This work of restoration can mean restoring them to the Edenic state of happiness. Such is "the fruit of harmonious action of all powers."

A Basic SDA Education Ingredient

Geraty points out:

Programs and curricula may differ, but basically the administrators and teachers in every Seventh-day Adventist educational institution will consider providing an environment for the holistic development of the students--physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual, and vocational.[9]

Mrs.

White admonishes that "some hours each day should be devoted to useful

education in lines of work that will help the students in learning the duties

of practical life, which are essential for all our youth."[10]

If this is so, then, schools should endeavor not to phase our work program

component in their curriculum despite its adverse effect to the financial

condition of the school. Instead,

schools should look for ways to generate income from other sources to finance

this program.[11]

Develop Work Ethics and Sound Habits

White says, "Manual training should develop the habits of accuracy and thoroughness…pupils should lean to economize time, and to make every move count."[12] The Berea College founders[13] give this assessment:

The work experience program is far more than an opportunity for student to earn part of the cost of his education, for it is based on the belief that there is quality in labor, which is essential to learning. It gives the participant a respect for work, good work habits, ability to cooperate with others, a feeling of self-reliance, a pride in accomplishment, and abilities of value in earning a living.

The WEP is a tool for developing correct attitudes. The UNESCO Panel[14] identifies work ethics as "industriousness, sense of responsibility, creativity, honesty, and diligence;" and proper work habits as "discipline, punctuality, work-safety habits, sense of perfection, and excellence."

If this is one mechanism to reverse the attitude of students towards the dignity of labor, this is worthy of consideration.

Skills Development

E. G. White asserts, "Every youth, on leaving school, should have acquired a knowledge of some trade or occupation by which, if need be, he may earn a livelihood."[15]

We desire that our youth are able to face the demands of a technologically advancing work-world by developing their competency in a skill or trade. It is a well-known fact that in developing countries, graduates who have skills on top of their academic degrees get better chance landing on a job and tend to remain longer on the job; and should there be any retrenchment, he is the last one to go. This was the gist of Mensah's introduction in his paper.[16]

Physical and Mental Health

White in school, we want our youth to be physically and mentally alert. Sister White admonishes that the first study of life should be to keep both the body and mind work harmoniously as it "cannot be to the glory of God for His children to have sickly bodies or dwarfed minds.[17]

The exercise of the brain in study, without corresponding physical exercise, has a tendency to attract the blood to the brain, and the circulation of the blood through the system becomes unbalanced.[18]

She also counsels us that "the whole system needs the invigorating influence of exercise in the open air. A few hours of manual labor each day would tend to renew the bodily vigor and rest and relax the mind."[19]

Moral Strength

There can be no greater reward than seeing our youth develop their moral powers to withstand the strong influence of a world going morally berserk.

There would now be more elevated class of youth to come upon the stage of action to have influence in molding society. Many of the youth who would graduate at such institutions would come forth with stability of character. They would have perseverance, fortitude and courage to surmount obstacles and such principles that they would not be swayed by wrong influence, however popular.[20]

Opportunity of Community Service

Dr. Wilson Evans, Dean of Labor for Berea College lists among four important values the students derive from the WEP as "community improvement--the working student is more aware of community needs and takes pride in a beautiful community."[21] Visger[22] postulates that "work and study programs equip men and women to reach beyond their campuses, to the community, and then to the world." Moore[23] reinforces this by saying that the WEP offers opportunities for service while Anderson[24] spells out that "such a program helps guide the students into an awareness of his responsibilities as a citizen."

Social Interaction/Interpersonal

Relationship

"The work experience education job site provides a setting where interpersonal skills can be developed through student-teacher-employer relationship," says Anderson. Kieslar[25] states that, "students must be given real opportunities to work with older and more experienced employees, with supervisors, with the public, and with other beginning workers." The UNESCO Panel[26] sees the desirability of teachers working with their learners," and Moore[27] expresses the same thought by saying the "WEP has thoroughly proved itself as a sound setting for development of intersect relationship of a high order, in a natural way."

Participation in Global Mission

At this time when the church is vigorously pursuing its objective to evangelize the world, more strategies are needed. One of the best strategies is equipping men and women with livelihood skills, which they could use as they are sent out to the community for missionary work. It is observed that in places where residents are predominantly Roman Catholics or are non-Christians, the gospel's penetration is almost impossible. However, when livelihood lectures and demonstrations are held, gradually prejudices are broken and the messages of truth are eventually spread out.

Improves Economic condition of Church Members

The students who have undergone experiential learning in school do not fear unemployment. They have resources within themselves to use to improve their economic condition. As they engage into private enterprise, their economic stability is strengthened.

Promotes Self-Realization and Fulfillment

The student, after graduation or perchance drops out of school before graduation, has acquired basic vocational skills which he can use to support himself and his family. He can be self-employed and self-dependent to help him achieve self-fulfillment in life.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The work experience program (WEP) has a rich historical beginning and is anchored on a solid philosophical foundation. This practice was based on a philosophy that education provides a balanced development of the mental, social, moral, spiritual, and physical powers of man to prepare him for a "complete living." Great men like Socrates, Comenius, Rouseau, Froebel, Pestalozzi, Dewey,[28] Gandhi,[29] Ellen White[30] and many others had advocated the philosophy of work and study. Furthermore, education should help man to internalize such a philosophy by facilitating experiential learning.

A work experience for youth introduces them to a world of work while in school to develop correct attitudes, habits and ethics; increase their mental and physical capacity; improve their health; and help them obtain basic skills; develop their vocational maturity; prepare them for occupation; promote their self-realization and fulfillment; provide opportunities for service and expose them to new patterns that cope with the modernization process.

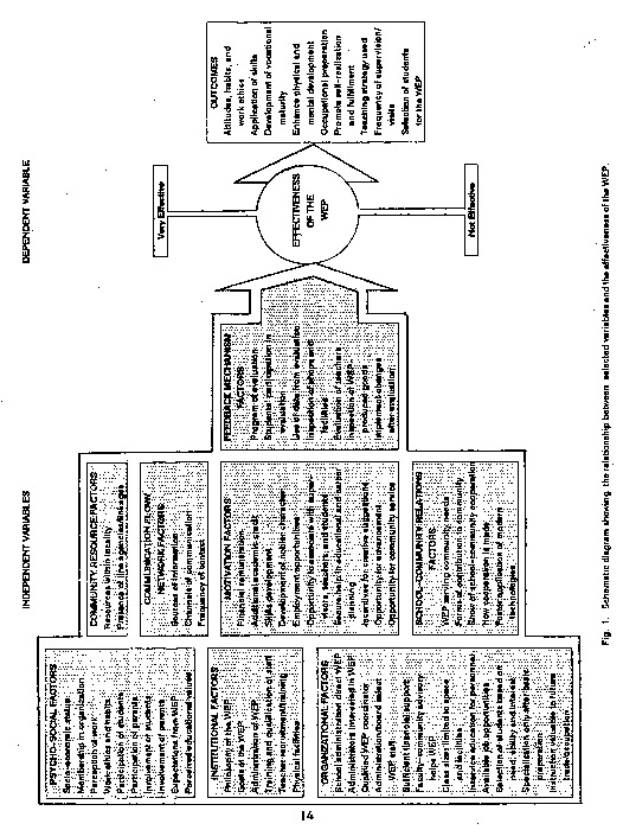

Notable educators and scholars reveal that effective work experience program does not happen by chance. This is influenced by some factors, which include psychosocial, institutional, and organizational, community resource, motivational, communication flow/network, feedback mechanism, and school-community relations.

Under the psychosocial factors the students' socio-economic status, membership in organization, perception of work, work ethics and habits, participation and involvement in the WEP, expectations and perceived educational benefits are considerations that dictate the students' work behaviors. Shertzer mentions that training and education are largely a matter of social class. The learning of manners . . .choice of educational goals and occupations are influenced by the class in which he lives.[31] Membership in organization also predicts better performance.[32] It has been observed that students' membership and participation in organization made them more participative in work activities and in decision-making. Lewin[33] reasons out that physical action is steered by perceptions, which runs true to the WEP. According to a UNESCO report, "work ethics and habits are indicated by industriousness, sense of responsibility, creativeness, diligence and discipline, as well as a sense of perfection or excellence." It is also assumed that participation and involvement in the activities and decision making process of the WEP spur better outcomes. Everyone who joins a program has his personal expectations and if he gets them by joining the WEP, these tend to improve his performance. His perceived educational value derivable from the WEP also stirs his desire for something better.[34]

The institutional factors that affect the work program include: philosophy, goals, administrative practices, training and qualification of the staff, teacher recruitment and training for the apprenticeship program, and physical facilities. As John Dewey points out, philosophy gives meaning and direction to our action.[35] Philosophy spells out the mission of the program. People usually out the mission of the program. People usually work harder and perform better when specific task goals are establish."[36] The role of an administrator is also crucial to the organization.[37] Researchers confirm that sound administrative practices make the program more functional.

One

of the many causes of failure of the schools to deliver the right training to

their students is the lack of teachers who possess the necessary skills,

commitment and dedication to do their jobs.

Others possess wrong attitudes toward the program of work that leave bad

influence. The recruitment of competent

and spiritually integrative teachers is vital to the WEP success.[38]

The inadequacy of physical facilities moderated the effectiveness of the work

program in the Philippines[39]

an some developing countries of the world.[40]

There are some organizational factors that influence the outcomes of the WEP. Barnard[41] says that, "central to the organization is the specialized administrative activity that serves the function of maintaining the organization in operation." NSSSE[42] included in its checklist for evaluating the program the following characteristics: support and direction by the administrative officers of the school, employment of qualified coordinators, financial support, and provision for in-service training of personnel.

Local community resources make up for most of the needed equipment and facilities in most training schools. This was shown by a UNESCO study report. Moreover, some government agencies tie up with private institutions to insure a supply of personnel needed to boost the economy of the nation. These resource factors are assumed to influence the WEP.

Stembridge[43] expresses, "Motivation activates human energy." It is assumed that people attend work-oriented programs to develop skills, augment income, and to increase their employment opportunities. Aderson says, "Motivation needs to begin before problems arise." In motivating, the following factors are vital: self-image, good example, progression and pay incentives, and personal fulfillment. Babcock[44] states that students are motivated to join WEPs to fulfill their social obligations such as associating with their supervisors, teachers, and fellow students. Some receive guidance and counsels from their teachers while others value the opportunity to do community service.[45]

Communication plays a very important role in the success of the WEP. Researchers indicate that failure to disseminate the usefulness of the work experience tends to mask the effectiveness of this innovative program. Many students join the WEP because they read, heard, and saw how the program changes lives for the better. Moreover, the parents understand better the aptitudes of their children and the importance of vocational education. This is true when progress reports are sent to the parents. As a result, parents' support ensues.[46]

Periodic evaluation is vital to the success of the training program. Moore[47] explains, "students usually reacts well to a challenge which leads them to excel at something." Employing a feedback mechanism insures that the WEP is on the right track.

The Committee on Curriculum Development of the National Association of Secondary School Principals[48] claims that a properly carried out work experience program makes a fine link between school and community. Raymond Moore adds that inter-institutional cooperation benefits those who participate in carrying out any program of activity. According to Anderson,[49]"Through cooperation between community and school, a student will gain better understanding of various occupations through the on-job training."

In this framework, it is conceptualized that relationships exist between the effectiveness of the work experience program and the following factors:

A. Psycho-social Factors

1. Socio-economic status

2. Membership in organization

3. Perception of work

4. Work ethics and habits

5. Participation and involvement in the WEP

6. Exceptions

7. Perceived educational value

B. Institutional Factors

1. Philosophy of the WEP

2. Goals

3. Administration

4. Training and qualification of staff

5. Teacher recruitment and training for the apprenticeship

6. Physical facilities

C. Organizational Factors

D. Community Resource Factors

1. Resources within the locality

2. Presence of line agencies/linkages

E. Motivational Factors

F. Communication Flow/Network

G. Feedback Mechanism

H. School-Community Relations (see Fig. 1)

SUGGESTED MODEL

Administrative

The president of the college shall serve as

the over-all chairman of the WEP. The

business manager looks into all financial planning and transactions. An over-all coordinator does the specific

details of scheduling in cooperation with the work/industries department

heads. The teacher shall serve as

supervisors.

Teacher-Student Volunteer Work

It

is suggested that all students and teachers in the college participate in at

least an hour daily for a volunteer

work on their field of choice. The

first two hours in the morning (7:00 to 9:00) is most suitable for

exercise. This does not include trade

courses, which are included in the daily class schedule. The following is a sample assignment.

|

Work Departments |

Teacher(s) In charge |

|

1. Food service |

a. Matron b. Assistant Matron |

|

2. Farm |

a. Farm Manager b. Agriculture teacher |

|

3. Ground and landscaping (GL) |

a. GL supervisor b. Sociology teacher c. Administrative secretaries d. English teacher |

|

4. Ground and concrete work. |

a. Masonry supervisor b. Garden supervisor |

|

5. Bakery |

a. Bakery supervisor b. Student assistants |

|

6. Gym and ground |

a. PE teachers |

|

7. Church and ground |

a. Church pastor & assistants |

|

8. Boys' dorm and ground |

a. Boys' dorm deans b. Deans of

students |

|

9. Girls' dorm and ground |

a. Girls' dorm deans b. Office secretary, dean of students |

|

10. Health service |

a. College physician b. College nurse |

|

11. Water service |

a.

Maintenance supervisor |

|

12. Woodwork

|

a. Industrial art supervisor |

|

13. Auto shop & ground |

a. Auto-shop supervisor |

|

14. Classrooms |

a. Classroom teachers b. Laboratory assistants |

|

15. Registrar's office |

a. Registrar b.

Assistants |

|

16. Library |

a. Librarian b. Library

assistants c. Communication arts teachers |

|

17. Other departments |

a. Supervisors |

CONCLUSIONS

A service-oriented denomination such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church needs to provide a program for its youth to make them able to respond to the various needs of the community. This calls for a balanced program of development, which sees to it, that this young people have the skills to employ for any contingency. The work experience program is a very viable approach. However, this should reach its goals or it will not do any good. Program administrators should know whether or not their program is effective. This paper also provides a framework for such an endeavor which, when thoroughly developed and enriched, will help them achieve satisfactory performances.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. A full-time work experience program coordinator should be appointed to study the various possibilities of making the WEP a successful training program.

2. Linkages with outside work agencies should be established.

3. Local human and material resources should be determined to include those who can provide technical counsels taking into consideration the following:

a. Invite retired teachers and engineers to teach or give guidance services.

b. Invite outstanding workers and veteran farmers to deliver lectures and share their experiences with the students.

c. Teachers and students work together to produce instruments and tools.

4. Parents should be involved in the planning various WEP programs and projects.

5. The program should be evaluated periodically.

6. The guidance services should be strengthened as to include career and trade information.

Information: A 16-page questionnaire on Asian setting

designed to determine the correlates of an effective work experience program is

available upon request from: Education Department, South Philippine Union

Mission, P.O. Box 208, 9000 Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines.

Endnotes