Institute for Christian

Teaching

Education Department of Seventh-day Adventists

BEYOND PROFESSIONAL CARING: TEACHING NURSING

STUDENTS THE ART OF

CHRISTIAN CARING

By

Nancy A. Fly

School of Nursing

Loma Linda University

Prepared for the

Faith and Learning Seminar

held at

Union College

Lincoln, Nebraska

June 1993

126-93

Institute for Christian Teaching

12501 Old

Columbia Pike

Silver Spring,

MD 20904, USA

At the core of contemporary

American nursing is "the order to care in a society that refuses to value

caring" (Reverby, 1987, p.1).

Historically, nurses have been viewed as caregivers in both the sense of

emotional contribution and clinical expertise (Benner, 1984). During the recent nursing shortage and with

anticipated changes in national health care, professional nursing has become

involved in developing a theory of caring that can be practical in client

interactions and teachable in schools of nursing. Caring, in its broadest sense, has become the watchword in

nursing practice.

The

use of the word "caring" in a professional sense can be related to

"three categories: attention to or concern for the patient; responsibility

for or providing for the patient; and regard, fondness, or attachment to the

patient" (Chipman, 1991, p.171).

Caring is "the willingness to provide support for others in times

of need" (Jacono, 1993, p. 93).

Caring

theory is difficult to delineate concretely.

The concept is illusive and seems to defy objective investigation,

though nursing researchers are continually pursuing new strategies to generate

data which will demonstrate the value of caring. Caring, as it relates to nursing, is predominantly a humanistic

philosophy. This philosophy has

enriched the profession, and yet, the Christian nurse must ask some basic

questions about its underlying presuppositions (Sire, 1990). How does Christian caring differ from purely

professional caring in terms of worldview, framework for practice, and teaching

methodology?

The

purpose of this essay is to answer these questions as well as to examine the

role of Christian nursing educators in preparing students for clinical practice

grounded on Christian values of caring.

Current Nursing Theory

The practice of

nursing is based on a variety of nursing theories. Though some experts argue that nursing, as a social science and

caring profession, should not be restricted by a particular paradigm (Robinson,

1992), present conceptual models are seemingly best understood in the context

of a fundamental nursing paradigm.

These models address the interrelationships among the descriptive

categories of nursing, person, health,

and environment (Fitzpatrick & Whall, 1989). The concept of God is not included in this metaparadigm.

Patricia

Benner and Jean Watson have developed models of caring which are currently

foremost in describing the essence of professional caring. Concepts of theses theories will be compared

and contrasted with each other as well as with a model for Christian caring.

Benner's

model places caring as a necessary component in her theory of skill acquisition

"from novice to expert" (Benner, 1984). She describes nursing

as an "enabling condition of connection and concern" (Marriner-Tomey,

1989, p.192) which implies a high level of emotional involvement in the nurse-client

relationship (Benner, 1989). Benner's

definition of person is "a

self-interpreting being, that is, the person does not come into the world

predefined but gets defined in the course of living life" (Marriner-Tomey,

1989, P. 192). Health is portrayed in terms of what can be assessed by the nurse

and includes wholeness as a description of well-being. Environment

is explained as situation which implies social significance and the interaction

of people within that situation (Benner, 1984).

Patricia

Benner speaks of the "power" of caring. Her description of the caring role involves the concepts of

transformative power, integrative caring, advocacy, healing power,

participative/affirmative power, and problem solving (1984). She emphasizes that nursing care is more

than the application of mere skill; it is relational and involves the nurse's

response as a human being, first, and then secondarily, in the nursing role

(1988). Benner's model seems to ascribe

primarily to a naturalistic worldview (Sire, 1990).

Another

nursing theorist, Jean Watson, focuses on nursing care that is humanistic and

individualized (Schroeder & Maeve, 1992).

Her philosophy and science of caring endorses a pantheistic view of the

cosmos (Carson, 1993). Watson's theory

addresses ten curative factors of nursing practice. They are:

1.

Formation of a humanistic-altruistic system of values.

2.

Instillation of faith-hope.

3.

Cultivation of sensitivity to one's self and to others.

4.

Development of a helping-trust relationship.

5.

Promotion and acceptance of the expression of positive and

negative feelings.

6.

Systematic use of the scientific problem-solving method for

decision-making.

7.

Promotion of interpersonal teaching-learning.

8.

Provision for a

supportive, protective, or corrective mental, physical, sociocultural, and

spiritual environment.

9.

Assistance with the gratification of human needs.

10.

Allowance for existential-phenomenological forces."

(Marriner-Tomey, 1989, p. 167-168)

Watson

writes of the need for a knowledge of caring which would examine the moral and

ethical implications involved in human caring in nursing (Watson, 1990). She views nursing as the practice of caring in which the nurse enters into a

transpersonal caring relationship with the client. This caring moment promotes and restores health as well as helps to prevent illness. Watson's idea of person contains the beliefs that human have potential for what they

may become and are free to make responsible choices. The environment is an

open system with internal and external variables which are at one with nature

and God. (Marriner-Tomey, 1989).

Both

Benner and Watson have made significant contributions which enhance the value

of professional caring. They have

helped to create an atmosphere within the nursing profession which values the

wholeness of human beings including their psychosocial and spiritual

needs. Many of their beliefs can be

accepted and affirmed by Christian nurses.

Yet a model of Christian caring in nursing is able to go beyond these

theories by basing nursing practice on a uniquely Christian philosophy.

Christian Caring

Historically, the

caring ministry of Christian professionals has been of interest to various

philosophers and theologians. Their

insights enhance the Christian nurses's view of the healing role. E.G. White writes that nurses "can

bring a ray of hope into the lives of the defeated and disheartened. Their unselfish love, manifested in acts of

disinterested kindness, will make it easier for these suffering ones to believe

in the love of Christ" (1912, p. 29).

Paul Tournier,

in his book The Healing of Persons, emphasizes the need for "real

inner transformation" as a prerequisite to health. "The source of all reformation of life

is in personal fellowship with Jesus Christ.

This is why I feel that the deepest meaning of medicine is still not in

'counseling lives,' but in leading the sick to this personal encounter with

Jesus Christ, so that accepting it they may discover a new quality of life,

discern God's will for them, and receive the supernatural strength they need in

order to obey it." (1965, p.212).

Judith

Shelly (1991) in her book, Values in Conflict, states: "nursing is no longer a Christian

profession. Not only are nurses

themselves becoming more pluralistic, but the very foundation of nursing is

shifting from its Christian roots.

Nursing theories are increasingly being based on New Age or secular

humanistic philosophies" (p. 63).

Shelly and Fish have conceptualized an approach to spiritual care which

emphasizes the need for meaning and purpose, love and relatedness, and

forgiveness based on faith in Jesus Christ (Shelly & Fish, 1988).

The

Catholic theologian, Henry Nouwen, has written for pastors about ministry in

contemporary society. In The Wounded

Healer, he speaks of principles of Christian leadership in the area of

human healing. Nurses are commissioned

to be leaders in caring. Thus these

principles can be applied in further defining the concept of Christian

caring. Nouwen's beliefs are delineated

as follows:

1. "Personal concern which asks one man

to give his life for his fellow man."

(Nouwen, 1972, p. 71).

Nouwen defines this sense of compassion as involvement in which the

whole person takes risk of entering into a painful situation without thought of

the possible hurt that may be experienced.

"The beginning and the end of all Christian leadership is to give

your life for others' (p. 72). This

thought offers an alternative beyond that of mere empathy which characterizes

professional caring (Montgomery, 1992).

Compassionate

connectedness is often displayed nonverbally by the nurse. For example, several students during

clinical lab were dealing with a variety of difficult patients in painful

situations. They had learned to be

professional in their caring and as non-traditional, more mature students, had

related empathetically with their clients.

Yet they felt they were "getting nowhere". They were all visibly touched, however, as

they observed their instructor become involved with the patients. "Something you do is different,"

they told her, as they observed the personal concern extended to the

patients. They noted that the patient's

responses were warmer and more positive as well. The students had used much of the same verbal communication, but

their manner was much less involved.

2. "A deep-rooted faith in the value and

meaning of life, even when days look dark"

(Nouwen, 1972, p. 71). This belief

finds meaning in human suffering even in despair and impending death. For a man or woman with this type of faith,

"every experience holds a new promise, every encounter carries a new

insight, and every event brings a new message.

But these promises, insights, and messages have to be discovered and

made visible. A Christian leader …

faces the world with eyes full of expectation, with the expertise to take away

the veil that covers its hidden potential" (p. 74, 75).

Christian

nurses might ask themselves – What meaning can be found by the family of an

Alzheimer's victim? How can I

facilitate faith for the family of a brain-damaged teen-ager or find promise in

the leukemia of a four-year old?

3. "Out-going hope which always looks for

tomorrow, even beyond the moment of death" (p.71). "Hope prevents us

from clinging to what we have and frees us to move away from the safe place and

enter unknown and fearful territory.

This might sound romantic, but when a man enters with his fellow man

into his fear of death and is able to wait for him right there, 'leaving the

safe place' might turn out to be a very difficult act of leadership" (p.77).

Hope

such as this gives the Christian nurses something very unique to offer to the

dying patient. This concept is

illustrated beautifully in the situation of a young mother dying of breast

cancer at home. The nurse sat with the

client, her husband, and three small girls in the early dawn as life ebbed

away. They talked of eternity, of God's

care for the future of the family, of plans for the heirloom quilts which the

talented young woman had nearly finished for the girls. Then they planned the funeral and spoke of

future memory parties where they would eat donuts together, just "the kind

that Mommy liked." Sharing this

kind of hope required involvement by the nurse as she placed her hand on the

husband's shoulder and held a tiny hand while a tear slipped down her cheek.

George

Akers, a Seventh-day Adventist educator, identifies behaviors in Christian

teachers which form a ladder of excellence going beyond the "mere

professional" (Akers, 1989, p.12).

Nouwen's principle can be applied to Christian caring in nursing which

also goes beyond professional caring.

These levels which were described in earlier text are: First,

professional caring; secondly, true personal concern or compassion; thirdly,

inspiration of faith; and finally, provision of hope. Each level requires progressively more involvement with the

client without thought of reward or possible personal pain.

According

to Nouwen, Christian caring is service which "requires the willingness to

enter into a situation, with all the human vulnerabilities a man has to share

with his fellow man" (1972, p.77).

So, is Christian caring then a form of codependency? This issue must be briefly addressed.

The

Christian's identity is found in a relationship with Jesus Christ. This enables the caregiver to serve clients

in an involved manner because of conscious choice rather than out of need or

shame (John, 1991). In addition to

having a sure identity, the Christian nurse experiences a type of spiritual

transcendence which finds a meaning in service that is not ego-centered. He/she retains a sense of Spirit-directed

connectedness with the client which is neither destructive to the nurse or the

patient. Also, the Christian caregiver

finds energy to cope with the stress of caring through a vital relationship

with God (Montgomery, 1992).

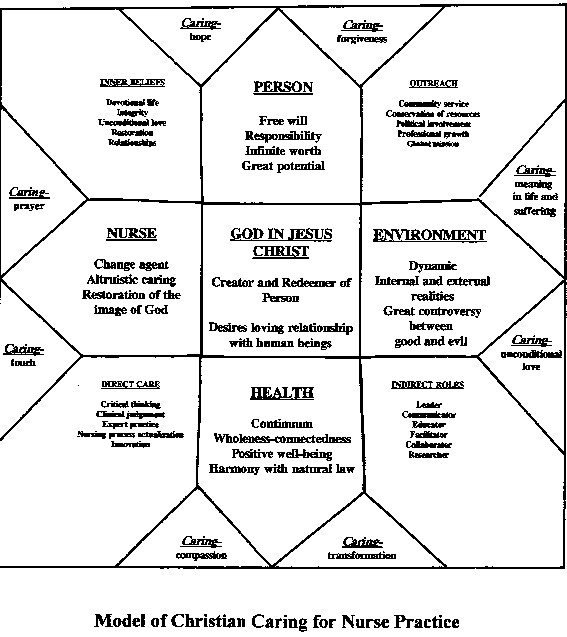

A

Christian framework of caring must include the concept of God in the person of

Jesus Christ. Jesus will be seen as the

Creator and Redeemer who offers restoration and forgiveness through

relationship with human being. Nursing will involve an altruistic,

caring relationship with clients which stresses change that will restore the

image of God in persons. Persons are created to reflect the

image of God with individual potential for continuous growth toward becoming

all that God intended for them to be.

Human beings have a free will which enables them to make responsible

choices. They are also of infinite

value. Health exists as a state of positive well-being involving the whole

person –mental, spiritual, physical, and psychosocial. It occurs on a continuum between high level

wellness and illness, and is significantly improved when the client's lifestyle

becomes increasingly in harmony with God's natural laws.

Environment is a combination and internal and external realities

which must interact with the individual.

These realities include the unseen great controversy between good and

evil as well as the possibility of eternal life in a perfect setting.

This

model of nursing practice will be enhanced by the uniqueness of Christian

caring which impacts every nursing interaction. Christian caring emphasizes the encouragement of a spiritual

transcendence which is based on a relationship with Jesus Christ rather than

existential phenomena or humanistic interchange. "And truly effective spiritual care will include humbly and

gently putting a person in touch with the triune of God" (Carson, 1993, p.

55).

Caring

in a Christian context will include the aspects of professional caring but it

will go beyond as it inspires hope in an eternal future (at Christ's second

coming), finds meaning in human suffering, offers forgiveness, "goes the

second-mile," and most importantly, encourages clients to find

unconditional love in Jesus.

Teaching Christian Caring

Nursing

education has become more committed to instructing students in the art of

caring. This movement over the past few

years has also provided a helpful basis for teaching caring from a Christian

perspective in schools of nursing whose mission reaches beyond secular standards

of professionalism.

"Care

is . . . conceptualized as values and as attitudes" (Symanski, 1990, p.

138). Nursing leaders have examined

caring as a value, which must be taught in the classroom and clinical setting. They see this instruction as essential to

promote caring professional behavior in the next generation of nurses

(Symanski, 1990). In a series of

interviews with both students and faculty within small liberal arts colleges,

caring was described as "a crucial dimension" of nursing education (

Miller, Haber, & Bryne, 1990, p. 132).

Caring should be the thread which runs through the nursing curriculum

from beginning to end.

To

educate in the area of Christian caring essentially means to teach unique

values which, when internalized, will affect nursing practice. Christian caring must involve moral

reasoning based on these values.

"Caring outcomes in practice, research, and theory depend on the

teaching of a caring ideology" (Cohen, 1993, p. 662).

A

few studies have been carried out which address moral reasoning in nursing

education. Further research is needed,

however, to evaluate the actual outcomes of learned values in terms of

performance in the practice setting after graduation. Christian caring becomes real only when it is displayed in involved,

caring behaviors between the nurse and the client. Most of the current literature and evaluation tools are directed

toward student attitudes rather than behavioral outcomes.

Cartwright,

Davson-Galle, and Holden (1992) hypothesize that humanistic existentialism is

the predominant philosophy upon which most nursing curricula is based. They suggest that moral development should

be encouraged in nursing education to create graduate nurses "who can

exercise personal and professional autonomy and accountability for moral

decisions" (p. 228) which influences their actions in the workplace. The use of Christian values in developing a

moral philosophy of nursing practice is not addressed.

In

a study of 79 registered nurses, Katefian (1981) used the Watson-Glaser

Critical Thinking Appraisal Test and Rest's Defining Issues Test to ascertain

the relationship between critical thinking and moral reasoning. She also examined the variable of

educational preparation and its effect on moral reasoning. Conclusions of this study indicated that the

higher the degree of critical thinking and level of education, the more

advanced the moral reasoning was inclined to be. 32.9 percent of the variance in moral judgment was attributed to

education and critical thinking. Consequently,

the development of critical thinking in nursing students would seem to enhance

the possibility for Christian caring.

Most

recently, Foster and Larson of Loma Linda University and Loveless of La Sierra

University (1993) discussed strategies for helping students in the development

of ethical-decision making, an integral part of Christian caring.

To

begin with, the student must have certain characteristics in order to make

sound ethical-decisions. These are:

1. Overall

physical, mental, emotional, social and spiritual health.

2. Ability

to see the perspective of another individual.

3. Skill

to decide whether or not an ethical problem actually exists.

4. Vision

to formulate possible responses.

5. Understanding

of ethical thinking in Western culture with consideration of both

"individual rights and community well-being" (p. 31).

6. Courage

to evaluate and modify decisions.

Specific

classroom strategies to encourage the development of these characteristics are

delineated by the authors. Active

learning can be encouraged through "small-group discussions, role playing,

case presentations, writing assignments, and debates. Specifically, faculty promote moral reasoning by listening,

asking thought-provoking questions, promoting peer-to-peer interactions, and

helping students reflect on how these concepts relate to themselves" and

their clients (p.32).

"Caring

in nursing education is conceptualized as an evolutionary, interpersonal

process between a nurse educator and a nurse student" (Sheston, 1990, p.

111). First of all, the instructor must

demonstrate caring behavior toward the students. As one faculty member expressed: " 'If we don't care, how

can we expect them (students) to care?' "

Then as student said: " 'It's like how they (faculty) are with us

is how we should be with our patients.' " (Miller, et al., 1990, p. 132).

The

teacher who cares will express genuine regard and empathetic understanding for

the students (Sheston, 1990). "The

caring teacher is professionally competent, has genuine concern for the student

as a studying person, has a positive personality, and is professionally

committed" (Halldorsdottir, 1990, p. 97).

Beyond this, the Christian professor of nursing will apply her inner

spiritual beliefs in all interactions with students in both the classroom and

clinical areas. Instructions in caring

requires "interpersonal demonstration and practice" (Sheston, 1990,

p. 113).

Class

content in Christian caring will incorporate concepts of "therapeutic

communication, appropriate use of touch, and nurse-patient relationships"

(Symanski, 1990, p. 138). The theories

of Benner and Watson will be heavily emphasized as they are compared and

contrasted with a Christian worldview.

Nouwen's principles of healing will be taught and applied in various

discussions of case studies and clinical situations. Students will be asked to analyze their own values and worldview

especially as these apply to the care of clients.

Gelazis

(1990) makes specific mention of the need for fostering creativity in nursing

students. She emphasizes the desire to

educate the full person as both a left and right-brained individual. In teaching care, the instructor can

incorporate the creative "use of poetry, use of humor, promotion of a

sense of wonder, work with other cultural groups (such as the homeless),

awareness of popular culture, and use of arts such as drama" (p.156). A Christian perspective with these

activities can make them especially meaningful. As the nursing educator encourages creativity in students, she/he

will also become more creative in developing new strategies to transmit caring

values.

Integrating

faith with learning in teaching the art of Christian caring requires unique

course content combined with visionary strategies of instruction. It necessitates close interpersonal

relationships with students and Christ-centered role-modeling.

Summary

Students in

Christian nursing programs should find that they will become nurses whose

caring goes beyond the mere professional level. They will build on existing theories of caring to include an

involvement with clients which supports faith, meaning, and hope. In essence, by caring in a uniquely

Christian manner, nurses will inspire their patients with the love of Christ.

References

Akers, G. (1989). The ministry of teaching. Adventist

Review, 166(20), 12-13.

Anderson, S.L. (1991).

Do student preceptorships affect moral reasoning? Nurse Educator,

16(3), 14-17.

Benner, P. (1984).

From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing

practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Benner P. & Wrubel,

J. (1989). The primacy of caring: Stress and coping in health and illness. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Carson, V.B. (1989).

Spiritual dimensions of nursing practice. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Carson, V.B. (Winter 1993). Spirituality: Generic or

Christian? Journal of Christian Nursing, pp. 24-27.

Cartwright, T.,

Davson-Galle, P., & Holden, R.J.

(1992). Moral philosophy and

nursing curricula: Indoctrination of a

new breed. Journal of Nursing

Education, 31, 225-228.

Chipman, Y. (1991).

Caring: It's meaning and place

in the practice of nursing. Journal

of Nursing Education, 30, 171-175.

Cohen, J.A. (1993).

Caring perspectives in nursing education: Liberation, transformation,

and meaning. Journal of Advanced

Nursing, 18, 621-626.

Fitzpatrick, J.J. &

Whall, A.L. (1984). Conceptual models of nursing: Analysis

and application. Norwalk, CT:

Appleton & Lange.

Foster, P.J., Larson, D.,

& Loveless, E.M. (1993). Helping students learn to make ethical

decisions. Holistic Nursing Practice,

7(3), 28-35.

Gelazis, R. (1990).

Creative strategies for teaching care.

In M. Leininger & J. Watson (Eds.), The Caring Imperative in

Education (pp. 155-165). New York:

National League for Nursing.

Halldorsdottir, S. (1990).

The essential structure of a caring and an uncaring encounter with a

teacher: The perspective if the nursing student. In M. Leininger & J. Watson (Eds.), The Caring Imperative

in Education (pp. 95-108). New

York: National League for Nursing.

Jacono, B.J. (1993).

Caring is loving. Journal of

Advanced Nursing, 18, 192-194.

John S.D. (Spring 1991). Whatever happened to caring?

Journal of Christian Nursing, pp. 18-22.

Katefian, S. (1981).

Critical thinking, educational preparation, and development of moral

judgement among select groups of practicing nurses. Nursing Research, 30, 98-103.

Marriner-Tomey, A. (1989).

Nursing theorists and their work (2nd ed.). St. Louis: C.V. Mosby.

Miller, B.K., Haber, J.,

& Bryne, M.W. (1990). The experience of caring in the

teaching-learning process of nursing education: Student and teacher

perspectives. In J. Leininger & J.

Watson (Eds.), The Caring Imperative in Education (pp. 125-135). New York: National League for Nursing.

Montgomery, C.L. (1992).

The spiritual connection: Nurses' perceptions of the experience of

caring. In D.A. Gaut (Ed.), The

Presence of Caring in Nursing (pp. 39-52).

New York: National League for Nursing.

Nouwen, J.M. (1972).

The Wounded Healer. New

York: Doubleday.

Orlick, S., & Benner,

P. (March 1988). The primacy of caring. American Journal of Nursing, pp.

318-319.

Reverby, S.M. (1987).

Ordered to care: The dilemma

of American nursing. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, J. (1992).

Problems with paradigms in a caring profession. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17,

632-638.

Schroeder, C., & Maeve,

M.K. (1992). Nursing care partnerships at the Denver Nursing Project in Human

Caring: an application and extension of caring theory in practice. Advances in Nursing Science, 15(2),

25-38.

Shelly, J.A., & Fish,

S. (1988). Spiritual care: The nurse's role (3nd ed.). Downer's Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

Shelly, J.A. & Miller,

A.B. (1991). Values in conflict: Christian nursing in a changing profession.

Downer's Grove, IL: Intervarsity

Press.

Sheston, M.L. (1990).

Caring in nursing education: A theoretical blueprint. In M. Leininger & J. Watson (Eds.), The

Caring Imperative in Education (pp. 109-123). New York: National League for Nursing.

Sire, J.W. (1990).

Discipleship of the mind: Learning to love God in the ways we think. Downer's Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

Symanski, M.E. (1990).

Caring in nursing education: a theoretical blueprint. In M. Leininger & J. Watson (Eds.), The

Caring Imperative in Education (pp. 137-144). New York: National League for Nursing.

Taylor, R. (1986).

Christian concepts: Core of professional nursing practice.

Tournier, P. (1965).

The healing of persons.

New York: Harper & Row.

White, E.G. (1912).

A call to medical evangelism and health education. Loma Linda, CA: Emerald Health and Education

Corporation.

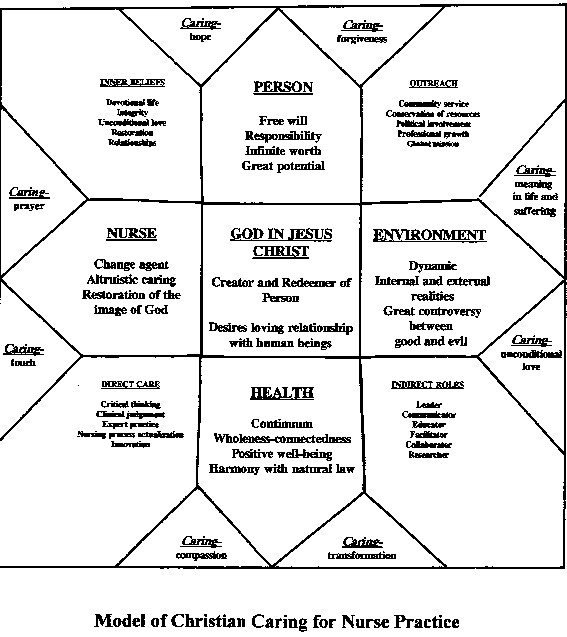

Caring Theories of

Nursing Practice

|

|

Benner

Primary of Caring

|

Watson

Theory of human

care

|

Christian Caring Model

|

Worldview

|

Humanistic

|

Neopantheistic

|

Theistic

|

|

Nursing's Metaparadigm (God)

|

General Spirituality

|

Spiritual

interconnectedness. One with nature. Existential phenomena.

Mysticism.

|

Jesus Christ

Creator

and Redeemer.

|

|

Nursing

|

Nurse-client relationship-- enabling condition of

connectedness.

Novice to expert.

|

Transpersonal

caring

interaction.

|

Change agent to restore the image

of God in persons.

|

|

Person

|

Self-interpreting.

Defined in the course of

living life.

|

Potential. Free

choice.

Connectedness with others

and nature.

|

Free-will.

Infinite value.

Created to reflect the

image of God.

|

|

Health

|

Assessment by nurse.

Wholeness.

Well-being.

|

Subjective.

Holistic.

More than the absence of

illness.

|

Wholeness.

Continuum.

Positive well-being.

Harmony with God's natural

laws.

|

|

Environment

|

Situation.

Implies social

significance.

Interaction of persons.

|

Open system.

Internal and external

variables.

Harmony with nature.

|

Internal and external realities.

Great controversy between

good and evil.

Future eternal life.

|

|

Caring

|

Responding first as a human being.

Relational.

Integrative.

More than skill.

|

Ten carative factors: –

include: values, hope, self sensitivity, trust, expression of feelings,

problem-solving, teaching, meeting human needs.

|

Adds to

Benner and Watson.

Person concern and

compassion.

Inspiration of faith.

Provision of hope.

|