Philosophy

The Most Useful of

All Subjects

Philosophy deals with the most basic

issues that human beings face–the

issues of reality, truth, and value.

By George R. Knight

The world is full of laws; not only in the physical realm, but also in the social. I have been collecting these enlightening laws for sometime.

Take SCHMIDT'S LAW, for example: "If you mess with a thing long enough, it'll break."

Or WEILER'S LAW: "Nothing is impossible for the man who doesn't have to do it himself."

And then there is JONES'S LAW: "The person who can smile when things go wrong has thought of someone to blame it on."

Of course, we wouldn't want to overlook BOOB'S LAW: "You always find something in the last place you look for it."

Having been enlightened by such wisdom, about 13 years ago I decided to try my hand at developing some cryptic and esoteric sagacity of my own.

The

result: KNIGHT'S LAW, with two corollaries. Put simply, KNIGHT' LAW reads that

"It is impossible to arrive at your destination unless you know where you

are going." Corollary number 1: "A school that does not come close to

attaining its goals will eventually lose its support." Corollary number 2:

"We think only when it hurts."

Those bits of "wisdom" were created in my days as a young professor of educational philosophy, when I concluded, as I still believe, that a sound educational philosophy is the most useful and practical item in a teacher's repertoire. Let me illustrate.

Addressing the Most Basic Issues

Philosophy deals with the most basic issues that human beings face–the issues of reality, truth and value. Our beliefs in those realms will determine everything else we do in both our personal and professional lives. Without a distinctive philosophy of reality, truth, and value, a person or group cannot make decisions, form a curriculum, or evaluate school or curricular progress. With a consciously chosen philosophy, however, one can set goals to be achieved and select courses of action to reach those goals. Thus, philosophy is the most useful topic for any educator to know.

Furthermore, a knowledge of philosophy's general outline (without its complexities and technical vocabulary) can be the most useful thing taught in the elementary and secondary curriculum. After all, our graduates must also make meaningful decisions in daily life.

With the above in mind, I will briefly describe the three main philosophic categories and illustrate how they relate to the practice of teaching (and living).

Metaphysics

One of the two most basic philosophy categories is metaphysics. This rather threatening-sounding word actually comes from two Greek words meaning "beyond physics." As such, metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of reality. "What is ultimately real? is the basic question asked in the study of metaphysics.

At first glance the answer to this query seems rather obvious. After all, average people seem to be quite certain about the "reality" of their world. If you ask them, they will probably tell you to open your eyes and look at the clock on the wall, listen to the sound of a passing train, or bend down to touch the floor beneath your feet. These things are, they claim, what is ultimate real.

But you can trip them up by asking, "What about God? Is He real? Does He exist? And if He does exist, what is His relationship to human beings and the 'real' world?"

Then ask them: "What about the universe itself? How did it originate and develop? Did it come about by accident or design? Does its existence have any purpose?"

That leads to questions about human beings: "Are they unique or merely highly developed quadrupeds? Are people born good, evil, or morally neutral? Do they have free will, or are their thoughts and actions determined by environment, inheritance, or divine proclamation? Do individuals have souls? And if they do, are those souls immortal?"

These are few of the questions that lie "beyond physics" in the realm of ultimate reality. None of the answers to these questions can be proved beyond the shadow of doubt. They are matters of faith and belief for all people and every political and educational system. Countless men and women have sacrificed and even died because of their commitment to certain beliefs about metaphysical questions. There are, in fact, no issues more crucial to human beings.

Metaphysics and Education

Even a cursory glance at basic metaphysical issues reveals their importance for every educational practice. It is crucial that every educational program be based upon fact and reality rather than fancy, illusion, or imagination.

Different metaphysical beliefs lead to differing educational approaches and even separate systems of education. Teachers' instructional methods will differ dramatically, depending on whether they view each student as Desmond Morris's "naked ape" or as a child of God. Likewise, discipline will be handled differently, depending on whether one thinks children are essentially good, as was asserted of Rousseau's Emile, or believes their goodness has been radically twisted by the effects of sin.

Why do Adventist churches spend millions of dollars each year for a private system of education when free public systems are widely available? Because of their metaphysical beliefs regarding the nature of ultimate reality, the existence of God, the role of God in human beings as God's children. Metaphysics is a major determinant of everything we as teachers do in the classroom.

Epistemology

Closely related to metaphysics is the issue of epistemology. Epistemology seeks to answer such basic questions as "What is true?" and "How do we know?" The study of epistemology deals with such issues as the dependability of knowledge and the validity of sources through which we gain information. Accordingly, epistemology stands–with metaphysics–at the very center of the educative process. Both educational systems and teachers in those systems deal in knowledge; they are engaged in an epistemological undertaking.

Epistemology has a direct impact upon education on a moment-by-moment basis. For example, assumptions about the importance of the various sources of knowledge will certainly be reflected in curricular emphases and teaching methodologies. Because Christian teachers believe in revelation as a source of certain knowledge, they will undoubtedly choose a curriculum and a central role for the Bible in that curriculum that differ substantially from curricular choices by public school teachers. The entire philosophic worldview of their faith will color the presentation of every topic they teach. That, of course, is true for teachers of all philosophic persuasions. It constitutes an important argument for educating our youth in Adventist schools.

Axiology

Teachers' belief about reality and truth will lead them to conclusions in the third great philosophic realm–axiology. Axiology answers the questions: "What is of value?" People are valuing beings. They prefer some things over others. Rational individual and social life is based upon a system of values.

The daily news tells us that there is no universal agreement on value systems. Different answers to the questions of metaphysics and epistemology produce different value systems.

Values define what a people or a society view as good or preferable in terms of behavior (ethics) and beauty (aesthetics). Therefore, churches have invested great effort and expense to pass on to the younger generation their beliefs about good behavior and beauty. These issues are flashpoints for controversy both in daily life and in the classroom when parents, teachers, and students disagree about various issues, such as television, music, or sexual behavior. The realm of axiology contains some of the most explosive human issues.

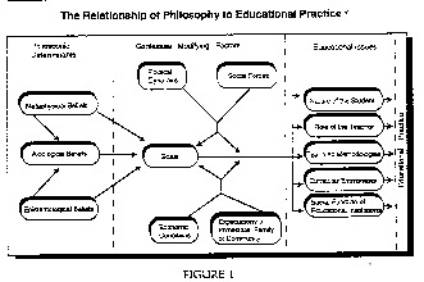

Figure 1 graphically illustrates the relationship between philosophic beliefs and practice. It indicates that a distinct metaphysical and epistemological viewpoint will lead the teacher to a value orientation. That orientation, with its corresponding view of reality and truth, will determine what educational goals are deliberately chosen by teachers as they seek to "act out" or implement their philosophical beliefs in the classroom.

As a consequence, the goals teachers choose suggest appropriate decisions about a variety of areas: students' needs the teacher's role in the classroom, the most important things to emphasize in the curriculum, the best teaching methodologies to communicate the curriculum, and the societal function of the school. Only when one has taken a position on such matters can appropriate policies be implemented.

As Figure 1 indicates, philosophy is not the sole determinant of specific educational practices. Elements in the everyday world (such as political factors, economic conditions, and expectations of the immediate family or community) also play a significant role in shaping and modifying educational practice. However, it is important to realize that philosophy still provides the basic boundaries for educational practice for any given teacher in a specific school. (The same can be said for other practical activities.)

Only when teachers clearly understand their philosophy and examine and evaluate its implications for daily activity in a Christian setting can they expect to be effective in reaching their personal goals and those of the school for which they teach. This is so because, as KNIGHT'S LAW declares: "It is impossible to arrive at your destination unless you know where you are going."

Corollary number 1 is important for every teacher and individual school: "A school [or teacher] that does not come close to attaining its goals will eventually lose its support."

Dissatisfaction with Christian education occurs when Adventist schools lose their distinctiveness and Adventist teachers fail to understand why their schools should be unique. Such teachers and schools should lose their support, since Adventist education without a clearly understood and implemented Adventist philosophy is an impossible contradiction and a waste of money.

Corollary number 2 is therefore crucial to the health and even survival of Adventist school–and the teachers in those schools. "We think only when it hurts." In too many places, Adventist education is already hurting. The greatest gifts we as educators can give to our church are (1) to consciously examine our educational philosophy from the perspective of biblical Christianity, (2) to carefully consider the implications of that philosophy for daily classroom activity, and then (3) to implement that philosophy consistently and effectively.

*From George R. Knight, Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective. 2nd ed. (Berrien Springs, Mich.: University Press, 1989), p. 37. Used by permission of University Press.