Institute for Christian Teaching

Education Department of Seventh-day

Adventists

A

CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW OF THE GEOGRAPHER'S WORLD

By

Harwood Lockton

Department of Humanities

Avondale College

Cooranbong, H.S.W., Australia

Prepared for the

Faith and Learning Seminar

Held at

Avondale College

Cooranbong, N.S.W., Australia

Junary 1990

070-90 Institute for Christian Teaching

12501 Old Columbia Pike

Silver Spring Md 20904, USA

INTRODUCTION

Geography is an ancient interest but a relatively

new discipline. Its roots go back at least to Herodotus (485-425 BC) but it

only became a formal academic discipline in the nineteenth century. Throughout

its long history, geography has had as its focus the observable fact that

people and landscapes vary from place to place across the Earth's surface. A

basic definition of geography is the study of places and their people-where

these places are, what they are like, how these places affect the people, how

he people affect these places, and what human activities go on in and between

these places.

At a more abstract level, geography is

the study of societies and space- how space affects the organization of

societies, and how in turn societies organize their spaces and indeed 'create'

space. Geography is simultaneously socially constitutive and socially

constituted.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a

Christian perspective on the nature of geography and is primarily intended for

fellow geographers at both the secondary and tertiary levels. However as

geography is only offered in a few Seventh-day Adventist Colleges, it is hoped

that this paper will be accessible to non-specialists especially in the social

sciences. From this examination it will

be shown that the secular paradigms offer a limited view of geographic reality

and that a Christian perspective brings an added and necessary dimension.

THE

NATURE OF GEOGRAPHY

The contemporary nature of geography can

be likened to a tapestry: a number of approaches or threads have been formative

as the discipline has developed over the past 2000 years. Since 1950 there has

been a rapid succession of approaches which some geographers have endeavoured

to fit into Kuhn's model of revolutionary paradigmatic change (Johnston 1983).

However, though at any one time there may be a dominant paradigm, there has not

been paradigm succession. Rather elements of the older paradigms co-exist, if

uncomfortably, with the newer ones. The threads are continuous. Five major

approaches will be briefly reviewed, in their chronological sequence.

1.

Regional

In the nineteenth and first half of the

twentieth centuries, regional geography held sway. Essentially it was a

description or inventory of the varied environments on earth and the people who

occupied these environments. The implicit philosophy was empiricism that

is that all knowledge is based on experience: the things others or we

experience are the only things that exist. The methodology employed was that of

data collection, from both observation in the field and secondary sources, and

the dissemination of the 'facts'. The observers were deemed to be objective and

value-free though many in practiced collected data that suited their sponsors,

for example commercial information from the new colonies for the imperial

governments (Johnston 1989:50).

This approach, especially at school

level, often degenerated into a 'capes and bays' approach – a sort of global

trivial pursuit. The National

Geographic's National Geography Bee in the USA and the Geographical Association's

Worldwide Quiz in the UK are really throwbacks to this empiricist capes and

bays approach.

Basically the regional approach answered

the questions, 'Where is it?' and 'What is it like, there?' But the questions

'Why is it like that, there?' or 'Why is it there?' are more tantalizing. Some regional geographers attempted to place

the observed facts into an explanatory framework to answer these higher order

questions and adopted Darwin's ideas about natural selection and the adaptation

by organisms to their environment. (1)

In environmental determinism,

these ideas were extended into the social arena whereby it was thought that the

nature of societies was determined in a unidirectional manner by the physical

environment of a given locality. For

example, it was suggested that the great Middle Eastern religions of Judaism,

Christianity and Islam originated in this largely desert region because there

was nothing in the landscape to occupy the mind and consequently meditation was

the only possible mental activity! Environmental determinism ignored the

reality that human-environment relations are two ways – each affects but rarely

'determines' the other.

Boundaries were assigned to the regions,

often with difficulty, so as to enclose areas that had some essential unifying

characteristic in common: usually a physical feature and commonly a river

drainage basin. This illustrates the

tacit acceptance of environmental control over people (Johnston 1989) even by

regional geographers who did not subscribe to environmental determinism.

Unfortunately, the concept of

environmental determinism persists in some primary school texts. A variant, social Darwinism, which sees

western societies as the epitome of progress and hence superior to so-called 'lesser

developed' societies is implicit in some Adventist mission report literature

("stone-age peoples"; "they do not even have computers")

even though the discipline of geography had largely discarded this concept by

the 1930s.

2.

Spatial

Analysis

Regional geography had lost its dominance

by the 1950s. Geographers were keen to

use more rigorous, scientific explanation after the debacle of environmental

determinism to answer the question 'Why there?’ This was particularly so in human geography: physical geography

for some time had used a more scientific approach and numerical data. The new approach in human geography was

spatial analysis, which is based on positivism (itself a development of empiricism). Because this approach relies on statistical

methods it is often referred to as the quantitative approach but the use of

statistics is only a means to an end in following the scientific method.

The fundamental assumption of the spatial analytic approach is that the methods of the physical sciences can be equally applied to the social sciences (Johnston 1986). The physical sciences – at least pre-Einstein and pre-Chaos theory – are predicated on the notion of order and consequently predictions can be made. Further, the observer is deemed to be value-free and the only valid knowledge we have is that derived from sensory experience, provided this experience can be verified by others. The aim is to generate law-like statements (or theory) by a process of model building, hypothesizing, and hypothesis testing " in a continuous looping procedure of organized speculation" (Johnston 1989: 51).

Deriving from the assumption that social

phenomena can be studied in essentially the same way as physical phenomena, is

the concept that the features of the human landscape – location of cities,

transport networks, land-use patterns etc – are organized according to

recognizable, repeated and ordered patterns.

Because the humanly created world is exceedingly complex, reality is

simplified in the spatial analytical approach, the key simplification being the

use of the 'economic man' (sic) concept imported from neo-classical

economics. Human beings are considered

to have complete knowledge of a given situation, to be driven by profit

maximizing motivations and make perfectly rational (i.e. economic)

decisions. The various spatial

analytical models rely on economic determinism: human agents have to respond to spatial

structures. People are no more than

machines operating in an economic environment.

Even from a non-Christian viewpoint this is untenable and the spatial

analytical approach was never accepted by all geographers even in its heyday of

the 1960s.

Another

important simplifying assumption is that of an isotropic plain – the real and

variegated landscape is reduced to a featureless, uniform plain. Thus places become part of abstract space

and the real world of variety disappears and may be the inherent interest of

geography to school students is lost. An exemplar of this approach is Haggett's

(1965) Locational Analysis in Human Geography.

3.

Humanistic

Various humanistic approaches have

been offered as a critique of positivism and its arid conception of space. Space is abstract but place is something

experienced. The humanistic approach

asks 'What does this place/landscape mean to those who live in it?'

Humanistic approaches attempt to promote understanding rather than explanation. In geography this means trying to understand the human world by studying people's relationships with nature and their spatial behavior, in terms of their feelings and ideas about place. The scientific method is rejected because; human geography at least, deals with the 'world of meaning' and not the 'world of things'. The role of the individual in creating their own ‘geography’ is central and so humanistic approaches focus on the actors. As Johnston says, "Humanistic geography does not describe a place from the outside but portrays what it is like to be part of that place" (1989: 56).

Because these approaches eschew formal

research and codification, it is difficult to analyze their philosophical bases

but idealism (all reality is a mental construction, an idea), phenomenology

(intuition is the only valid source of knowledge), and existentialism (reality

is created by free human agents) have all been used by various humanistic

geographers (Holt-Jensen 1988: 78-81, 107-111). Yi-Fu Tuan's Landscapes of Fear (1980) is an exemplar of

the humanistic approach. At the school

level these approaches are popular as they coincide with the ideals of

child-centered education.

4.

Radical

This approach, also known as the

political economy approach, has been used widely in the 1980s in analyses of

industrial location, global inequalities and urban problems. It is currently the dominant paradigm in

human geography and calls for revolutionary theory in tandem with revolutionary

praxis. The goal is a social revolution

to replace the apparently oppressive structures of capitalist society with a

socially just society. The central

questions are 'who benefits/loses because of this location decision?' and 'How

can this place be changed so that all benefit?' Storper and Walker's The

Capitalist Imperative (1988) is an exemplar of this approach.

The dominant form of radical geography is

Marxist, particularly structural Marxism.

Underlying this approach is a Materialist analysis of society:

for humans to live, the production of objects necessary for physical needs is

essential. The material or economic

dimension (the base) of society is paramount and the other dimensions such as religion,

education, politics (all part of the superstructure) are merely determined by

the base though they exist to support and legitimize the capitalist mode of

production.

Marx proposed five modes of production of

which capitalism is the fourth in his evolutionary sequence. The essence, according to Marx, of the

capitalist mode of production is the antagonistic yet mutually necessary

relations between two classes, the capitalists (or owners of the means of

production) and the workers. This antagonism generates conflict and ultimately

revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist class. However capitalists also

compete with each other in a 'survival of the fittest' manner.

Structural Marxism is quasi-determinist:

human agents are little more than puppets manipulated by the economic base

(Holt-Jensen 1988:114). This approach

conflicts with the humanistic approach, which maintains that individuals are

free to act and that there are no constraining external circumstance to limit

their actions. According to Marx, the

capitalist exploits his/her workers because of the imperatives of his/her class

position and so as an individual is not to blame. Social structures are deemed to be more significant than human

agency: determinism seems to haunt geographic explanation.

Paradoxically in view of Marx's own moral

indignation at the plight of factory workers in nineteenth century England,

there is no basis for morality in his schema.

Religion, a part of the superstructure, is a creation of the capitalist

class to divert the proletariat from the real issues of their oppressed

condition.

5.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism is a currently emerging

approach or collection of approaches (see Soja 1989). Essentially postmodernism is a critique of the

Enlightenment. It can not accept the

authority of any one paradigm or approach to be the answer: there can be no

Grand Theory (Dear 1988). In geography

it is a movement beyond the modern (such as spatial analysis and radical

geography) and "an invitation to construct our own human

geographies" (Gregory 1989:69).

There is as yet no clear epistemology, in part because the approach

appears to be combinational and eclectic involving geography, history,

sociology and the critical school, especially Habermas. Peet and Thrift (1989:23) suggest that this

approach assumes:

". . . that meaning is produced in language . . . that meaning is not fixed but is constantly on the move . . . and that subjectivity does not imply a conscious, unified, and rational human subject but instead a kaleidoscope of different discursive practices. In turn the kind of method needed to get at these conceptions will need to be very supple, able to capture a multiplicity of different meanings without reducing them to the simplicity of a single structure."

A

fascinating exemplar of a postmodernist approach is Soja's interpretation of

contemporary Los Angeles (1989: chapter 9).

6. Key Questions in Geography

These differing paradigms have

contributed richness to the discipline of geography. The central focus is still the study of the Earth's surface as

the space in which people live in specific places and environments. The key questions, which summarise

geographic inquiry, are:

1.

Where are

people and their activities distributed on the Earth's surface?

2.

What are

the places and environments like where these people and their activities are

located?

3.

What is the

nature of the relationships between people and their environments?

4.

How do the

people perceive their environments?

5.

Why are

these people and their activities located in these places?

6.

Who decides

and who benefits or loses from the location decisions that have been made?

A

CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW

According to Walsh and Middleton

(1984:35) a worldview should answer four fundamental questions:

1.

Who am I?

2.

Where am I?

3.

What is

wrong?

4.

What is the

remedy?

A biblical worldview is sketched here

that answers these questions and will be used to test the current philosophies

and paradigms in geography. (2) The organising theme for this biblical

worldview is the major events in salvation history.

1.

The Great

Controversy

This acknowledges the existence of God,

the central fact of the Christian worldview.

Further, it identifies the source and origin of Satan and evil and hence

sin in humanity. The Great Controversy

is a conflict between God and Satan, between good and evil. As C. S. Lewis points out so aptly: "There is no neutral ground in the

universe: every square inch, every split second, is claimed by God and

counterclaimed by Satan" (quoted in Walsh and Middleton 1984:71). This conflict began before the Creation of

this world and will continue until the Eschaton., A Christian worldview thus has eternal and supernatural

dimensions.

2.

Creation

The act of Creation clearly identifies

God as the creator of our world and the universe. This world is part of God's

kingdom and He is Lord and Sovereign. Christians should thus have a high view

of their fellow humans as all were created in the image of God and hence are

equal before God. The natural world is

also God's creation; we are called to be environmental stewards (see Lockton,

forthcoming). As God's representatives we are mandated to reveal His love,

mercy, justice and holiness, or in other words, His image.

3.

Fall

Though created perfect, this world,

including both the natural and social orders, has been contaminated and warped

by evil. The locus of the Great

Controversy was switched from heaven to earth at the Fall. This changed the nature of human nature and

resulted in a series of broken relationships: humans with God, humans within

themselves, humans with other humans, humans with their environment. Every aspect of human society and of nature

has been changed and sin is not only personal and individual it is also

corporate and infects social structures.

The Fall also shows that human beings were created with the capacity to

make moral choices.

4.

Redemption

Christ's salvation offered at the cross

can begin to restore the relationships broken at the Fall. However that restoration depends upon human acceptance

of Christ's offer and it will never be full and complete this side of the

Eschaton. The role of the Holy Spirit is central in this restorative process.

5. The Eschaton

Earth history is linear and will

culminate in the second advent of Christ.

Only at this event will the relationships broken at the Fall be fully

restored as the Great Controversy is ended, Satan defeated and sin

eradicated. After the second advert

there will be a new creation, a new perfect order.

While the Creation and Redemption give us

cause for optimism about human affairs, the Great Controversy and the Fall

provide a realism that is missing in many of the Christian transformist visions

for the world (see Walsh and Middleton 1984).

We cannot achieve complete transformation (whether Calvinist or Marxist)

of this world this side of the Eschaton.

A

CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVE ON CONTEMPORARY GEOGRAPHY

As the regional approach has almost

disappeared and the emergent postmodernist approach is not yet clearly

delineated, the three contemporary approaches of spatial analysis (positivist),

humanistic and radical (structural/Marxist) will be examined from a Christian

perspective. Johnston (1989:62) has

referred to these approaches as part of the empirical, hermeneutic and critical

sciences respectively.

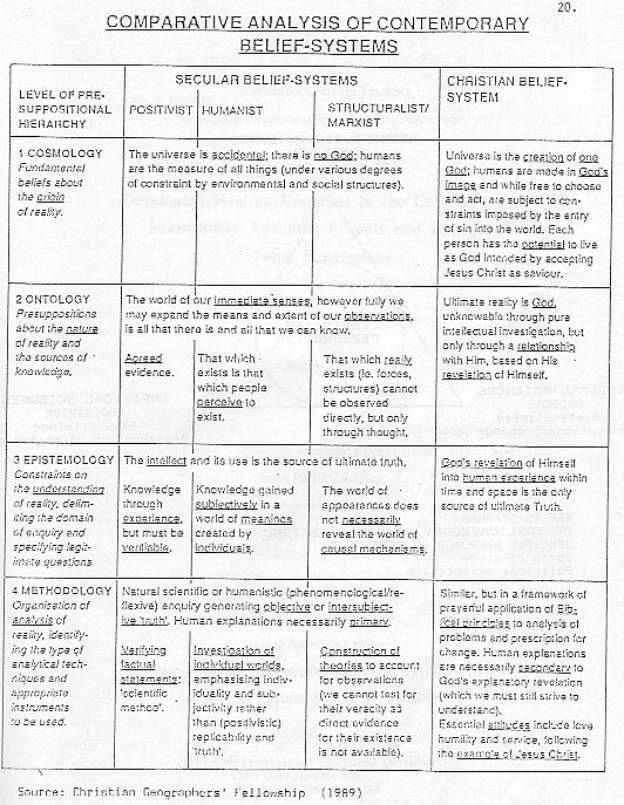

Use is made of a preliminary analysis

produced by the newly formed Christian Geographers' Fellowship (Figure 1),

which is structured around the presuppositional hierarchy of Harrison and

Livingstone (1980). This moves from the

highest level, Cosmology through the successively lower levels of Ontology,

Epistemology and Methodology.

From a Christian critique the three

approaches have much in common. At the

cosmological level there is no God and the origins of the world are therefore

seen as accidental and not purposeful.

In empiricism and positivism there is no room for God as nothing is a priori (Holt-Jensen 1988:92). Human nature likewise is seen as accidental

in origin and so without any existential purpose. For the Christian this is a partial view that denies human beings

their full God-given humanity. Human

beings were created in the image of God and have both potential and

choice. Again we see that the secular

paradigms do not have a complete view of people.

At the ontological level the secular

paradigms place humans in a primary position, people are the ultimate source of

knowledge, whereas the Christian viewpoint places humans in a secondary

position as God is above His created beings.

"You made him a little lower than the heavenly beings" (Psalm

8:5, NIV). Consequently for Christians

there are sources of ultimate knowledge beyond themselves, namely God's

revelation to us in Christ and the Word.

At the epistemological level "man is

the measure of all things". The

eternal and moral dimensions are ignored in these secular paradigms.

At the methodological level there is

probably no difference between the selection of appropriate techniques by

either the secular or Christian perspectives.

The difference is in the conclusions drawn from the analysis, whether

human explanations are seen as primary or secondary.

Further criticisms can be made of the

individual non-Christian approaches.

Spatial analysis elevates the economic to center position in exactly the

same way as does Marxism. Human nature

is diminished in the spatial analytical view as human agents can only act

passively under a deterministic structure.

Humans are only machines, part of a mechanistic system where morality

and ethics have no place and so the "best" or optimum location (the

central concern of most of the models in this approach) is seen solely in terms

of profitability and not in terms of, for example, environmental or social

impacts.

The humanistic approaches criticize the

positivistic approach for many of the same reasons as does the Christian

perspective (see Ley 1980) but they swing the pendulum too far in the human

agency direction so that individuals, and not God are central. Each person is totally free as regards his

or her nature and destiny (Sire 1988:111) and so there is no absolute ethical

framework within which humans should act.

The Marxist approaches must be critiqued

at the fundamental level of being materialist.

Human life is more than the material.

"Man does not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes

from the mouth of God" (Matthew 4:4,NIV).

As with the spatial analytical approach the Marxist approach is

deterministic and has a low view of human nature. (3) Consequently human agency

is very limited, being constrained by the imperatives of the mode of production

and the structures of society. Societal

and individual change are essential components of both Marxism and Christianity

but in the former the structures of society must be changed in order to produce

the 'new man', whereas according to Christianity conversion change of the

individual is a prerequisite for societal change and improvement. Evidence from the communist countries

suggests that the Marxist 'new man' is elusive. However, this line of reasoning can be turned back on Christians

and 'Christian nations.’ A further

Christian criticism is that Marxist solutions accept immoral means to achieve

their desired ends because there is no basis for morality.

The Marxist approach is valuable in that

it has directed geographers to aspects of society and space that were

previously ignored – it identifies what is wrong although it does not get to

the root cause of the wrong. Ley (1974)

has provided a penetrating Christian critique of the Marxist perspective in

regard to the explanation of inequality in the city. (4) As he concludes

"...it is privatistic iniquity, not social inequity, which is the root

cause of evil in the city" (page 71).

It needs a Christian perspective to extend the analysis and arrive at

ultimate causes in terms of the Fall and the existence of evil. Only then can viable solutions be

formulated.

Each of the approaches in the discipline

of geography has its strengths and usefulness.

But each approach is seen by its practitioners in exclusive terms and

reality can not be encompassed by any one of these approaches, especially when

that reality includes the supernatural dimension as outlined in the Christian

worldview. Figure 2 attempts to summarise some of the key features of these

approaches. Christians are generally

comfortable with the empirical sciences but should be able to utilize both the

hermeneutical sciences in order to better understand people and the critical

sciences to critique the way in which society actually operates (the prophetic

role?). However we should not see these

approaches "as decisive, or as the only relevant analyses" (Gill

1989:66).

THE

VALUE OF GEOGRAPHY IN CHRISTIAN EDUCATION

Geography should be an integral part of

education in Christian schools for a number of compelling reasons. In terms of content, the discipline aids the

student in understanding the local environment in which he/she lives. It locates that local environment in the

wider global system in which all places, and people, are interdependent.

But it is in terms of values that

geography has a crucial role in Christian education. Geography in Christian schools has a trinity of interests: God,

the planet and people. Two core value areas

derive from these interests (Lockton 1990).

First, concern for the state of the environment, whether local, national

or global. It is paradoxical that

Seventh-day Adventists with their concern for the veracity of the creation

account have not been as concerned with the stewardship of that creation

(Lockton, forthcoming). Geography has a

long tradition of such concern. A

Christian understanding of environmental issues is particularly needed at the

present time as the 'green' movement has a distinctly pantheistic tone. Perhaps this is the time to call humanity to

"Fear God and give Him glory . . .worship Him who made the . . . the earth" (Revelation 14:7,

NIV).

Second, concern for the plight and

condition of people in other places.

Christ gave us the Great Commandment – to love others – and geography

can help in creating empathy and compassion for the human condition, especially

in distant places. Christ also gave us

the Great Commission – to go into the entire world. Again it is paradoxical

that Seventh-day Adventists with the most global of Protestant mission programs

have largely ignored geography (5).

Yet Ellen White (1903:269) called for an education that studied

"all lands in the light of missionary effort" that students might

"become acquainted with the peoples and their needs".

Contemporary geography and Christianity

are showing a convergence of interest and concern – for the state of the

environment and the persistent and mammoth problem of global inequality. Geography should be prominent in all

Christian schools.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has outlined the philosophical

presuppositions of various approaches in the discipline of geography. Several of these presuppositions conflict

with those of a Christian worldview.

However this is not unique to geography and in fact offers the Christian

teacher an excellent opportunity to help his/her students better understand

conflicting worldviews and to see how their Christian faith relates to their

academic pursuits.

I also contend that the Christian

critique enhances and enlarges the otherwise restricted, partial viewpoints of

the secular approaches. Reality is

larger and more complex than they admit.

END NOTES

1.

Darwin's

influence upon the discipline of geography has been traced by Stoddart (1966)

and Livingston (1985).

2.

The

difference between Christian and Adventist viewpoints has not been defined in

this paper, though the Great Controversy motif is chiefly an Adventist

concept. The Eschaton, especially its

imminence, while not unique to Adventists is not held by all Christians.

3.

Marxism and

positivism developed from empiricism and all three are part of the broad

category of naturalism (see Sire 1988).

4.

Other

Christian critiques in geography have been offered by Houston (1978) on

relationships between people and land/territory and by Wallace (1978) on the

presuppositions of economic geography.

5.

History has

always been stronger than geography in the SDA educational system, presumably

because of the latter's relationship to prophecy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christian

Geographers' Fellowship Report,

March 1989 (c/- Matthew Sleeman, St. Catherine's

College, Cambridge CB2 1RL, UK).

Dear, M. 1988 The postmodern challenge:

reconstructing human geography. Transactions

of the Institute of British Geographers, 13:262-74.

Gill, D.W. 1989 The

Opening of the Christian Mind, IVP, Downers Grove, Illinios.

Gregory, D. 1989 Areal Differentiation

and Post-Modern Geography in Gregory, D. & Walford, D. (eds) Horizons in

Human Geography, Macmillan, Basingstoke, U.K.:67-96.

Haggett, P. 1965

Locational analysis in Human Geography, Arnold, London.

Harrison, R.T & Livingstone, D.N.

1980 Philosophy and problems in human geography: a presuppositional approach, Area,

12: 25-31

Holt-Jensen, A.

1988 Geography: History and Concepts, Paul Chapman Publishing, London.

Houston, J.M. 1978 The concepts of 'place'

and 'land; in the Judaeo-Christian tradition, in Ley & Samuels (eds),

Humanistic Geography: Prospects and Problems, Croom Helm, London: 224-237.

Johnston, R.J. 1983 Geography and

Geographers: Anglo-American Human Geography since 1945, Ed Arnold, London.

Johnston, R.J.

1986 Philosophy and Geography, Ed Arnold, London.

Johnston, R.J. 1989 Philosophy, Ideology

and Geography, in Gregory, D & Walford, R (eds) Horizons in Human

Geography, MacMillan, Basingstoke, U.K.: 48-66

Ley, D. 1974 The city and good and evil:

reflections on Christian and Marxist interpretations, Antipode, 6:66-74.

Ley, D. 1980 Geography Without

Man: a Humanistic Critique,

Geography department Research Paper #24, University of Oxford.

Livingstone, D. 1985 Evolution, science

and society: historical reflections on the geographical experiment,

Geoforum, 16: 119-130.

Lockton, H.A.

Forthcoming. Creation: the neglected

doctrine? Ministry

Lockkton, H.A. 1990 Geography's impact on

human values, Journal of Adventist education, Feb-Mar: 10-13,44-45.

Peet, R. & Thrift, N. 1989 Political

economy and human geography in Peet, R & Thrift, N. (eds) New Models in

Geography, Unwin & Hyman, London, Vol 1:3-29.

Sire, J.W. 1988 The Universe Next

door: A Basic World View Catalogue, IVP, Downers Grove, Illinois.

Soja, E.W. 1989 Postmodern

Geographies, Verso, London.

Stoddart, D.R.

1966 Darwin's impact on Geography, Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogrs., 56:683-698.

Storper, M.

& Walker, R. 1988 The Capitalist Imperative, Blackwell, Oxford.

Tuan Yi-Fu 1980 Landscapes

of Fear, Blackwell, Oxford.

Wallace, I. 1978 Toward a humanized

conception of economic geography, in Ley & Samuels (eds) Humanistic

Geography: Prospects and Problems, Croom Helm, London: 91-108.

Walsh, B.J.

& Middleton, J.R. 1984 The Transforming Vision, IVP, Downers Grove,

Illinois.

White, E.G. 1903

Education, Pacific Press Publishing Association, Mountain View,

California.

HERMENEUTIC SCIENCES HUMANISTIC Individual: feelings Anarchy

EMPIRICAL SCIENCES

POSITIVISM Nature: things

Preservation of status quo CRITICAL SCIENCES RADICAL Society: classes

Revolutionary change

KEY TO

DIAGRAM

GENERAL

CATEGORY OF SOCIAL SCIENCE

SPECIFIC

APPROACH IN GEOGRAPHY

Focus of

study

Political

Orientation

FIGURE 2 RELATIONOSHIPS BETWEEN CRHISTIAN

AND SECULAR

PHILOSOPHIES IN GEOGRAPHY AND THE SOCIAL

SCIENCES